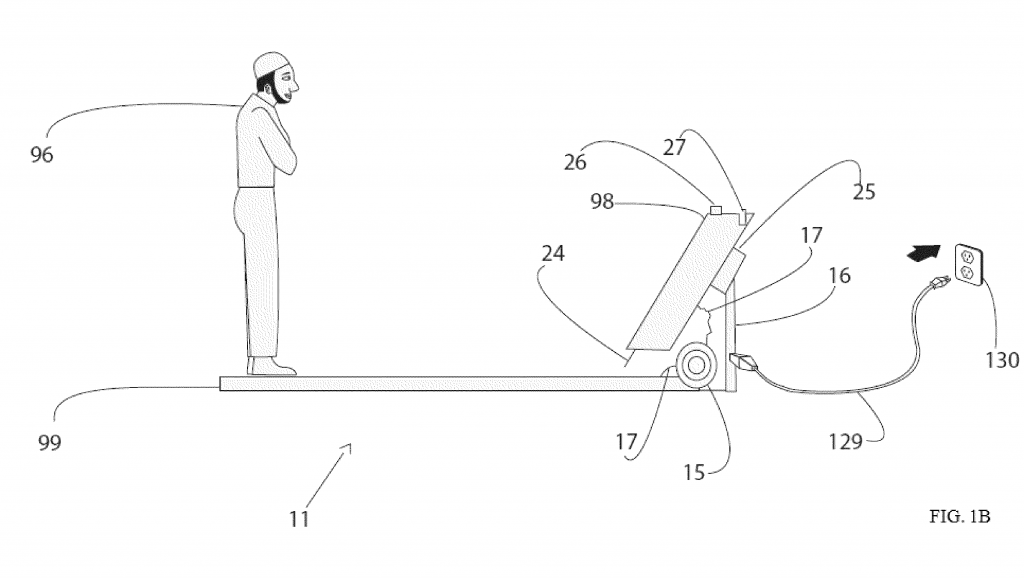

A machine that I’ve taken to calling “Pray Pray Revolution” stands out, among hundreds of other prayer systems and devices described in patent applications, due to its inventor’s precisian approach to ritual movement. In 2009 Wael Abouelsaadat, a graduate student in Computer Science at the University of Toronto, filed an application for an interactive prayer system with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. His system for “enhancing prayer” has three key components. First, it has a prayer rug equipped with force sensors and vibrating motors. This pressure-sensitive pad registers when and in precisely what order a user’s knees, hands and forehead touch the ground. Second, the system comes equipped with a camera that takes digital photographs of the user in motion. Through a posture detection technique involving the use of geometric modeling tools, a software program establishes a kinematic model of his or her bodily poses. Finally, this system also features a screen that coordinates the display of scriptural passages—in the original script of revelation or liturgy, as well as in transliteration and translation—with the performance of particular gestures of prayer.

Abouelsaadat’s invention may seem unremarkable to a generation of gamers and engineers familiar with Konami’s video game Dance Dance Revolution and, more pertinently, Microsoft’s innovative motion-sensing device for its Xbox 360 video-game console, Kinect. From a technological perspective, it is indeed a fairly straightforward application of recent innovations. What I find remarkable, however, is the fact that Abouelsaadat approaches ritualized prayer from an engineer’s perspective as a modern problem that can be solved by modern technology. “It is becoming increasingly difficult to schedule ritual,” he claims, “with the rapid life pace of the modern world.” Laypersons lack the knowledge and skills to perform prayer movements correctly and in perfect synchrony with the recitation of apt formulas derived from sacred texts. They want to “customize their ritual experience with minimum time spent in educating themselves.” His praying machine would in particular provide Muslims pressed for time but eager to learn how to pray perfectly with the necessary technological assistance.

Central to this conception is an obsession with error. Mistakes in the performance of the ritual “could invalidate the prayer.” Prayer counts as valid in Islam only if every posture and the entire sequence of steps conform exactly to prescribed norms. So Abouelsaadat designed his machine to detect errors. When a user omits a required step or commits a lapse by introducing a step that is not indicated by the program, the disc motors embedded within the prayer rug begin to vibrate.

Central to this conception is an obsession with error. Mistakes in the performance of the ritual “could invalidate the prayer.” Prayer counts as valid in Islam only if every posture and the entire sequence of steps conform exactly to prescribed norms. So Abouelsaadat designed his machine to detect errors. When a user omits a required step or commits a lapse by introducing a step that is not indicated by the program, the disc motors embedded within the prayer rug begin to vibrate.

If anxiety about correct performance is a characteristic of the religious life of modern Muslims, as of other believers who strive to observe very complex ritual traditions, reaching a spiritual experience while praying is still a goal for many. Even a Muslim engineer such as Abouelsaadat worries about reducing prayer into a mere mechanical sequence of bodily gestures. In his view of ritual, which owes something to Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi’s Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, it is critical that technological systems and methods to enhance prayer not disturb the enchanted mental state that can supposedly be accomplished through unmediated ritual immersion. Abouelsaadat’s claim to solve the problem of technological mediation during a ritual performance strikes me as implausible, however, if not disingenuous. Surely, the vibrating disc motors, triggered by an error, would disrupt the user’s concentration and negatively affect the experience of prayer. Indeed, even in a flawless performance, the user could easily suffer from an exhilarating anxiety over setting off a correctional mechanism. The experience of learning to pray in this sense would be difficult to distinguish spiritually from the experience of mastering a dull video game. Just imagine endlessly dancing “La Macarena” or “Gangnam Style” on the Xbox, with the sound turned off and the fear of God in your heart.

The really exciting thing about Abouelsaadat’s invention is that it offers us a glimpse into the future. As a historian I am of course aware of precedents. From medieval astrolabes to digital prayer clocks, multiple instruments have helped Muslims perform the work of religion. I am also aware of the fact that Abouelsaadat’s prayer system will be expensive, simply unaffordable for most Muslims, and therefore very likely troubling to those who preach that Islam is an egalitarian religion. Yet this system incorporates all the intricate details and myriad prescriptions that characterize Muslim prayer rites, which in the past could only be learned by imitating others or by taking lessons from ritual experts. For ages, novice and casual worshippers had no choice but to perform rituals while suffering from a nagging worry about messing up in public. But now, finally, affluent Muslim technophiles will be able to learn how to pray perfectly without any human interaction—thanks to a machine.

Tags: Islam, prayer console, technology, video games