[Editor’s Note: This post is part of the ongoing conversation in response to “Praying with the Senses,” Sonja Luehrmann’s portal into Reverberations’ unfolding compendium of resources related to the study of prayer.]

Partly in response to the prayer portal “Praying with the senses,” Anderson Blanton and Sarah Riccardi and Aaron Sokoll have started an interesting discussion of how to theorize the role of material objects as “media for connectivity” (Riccardi and Sokoll) or bodily “interface” (Blanton) for prayer. I agree with most of what the three authors say, but would like to use an example from my previous research on Pentecostal Christians in Russia to explain what is pushing me away from making the connective properties of sacred objects the sole focus of our exploration of the sensory workings of Eastern Christian prayer. In short, I think that the “wow-effect” that an emphasis on materiality brings to studies of Pentecostalism and other branches of Protestant Christianity isn’t there for Eastern Orthodoxy. In Eastern Orthodoxy, as Riccardi and Sokoll point out, the significance of the material holy goes “back to key councils and writings of … saints and theologians.”

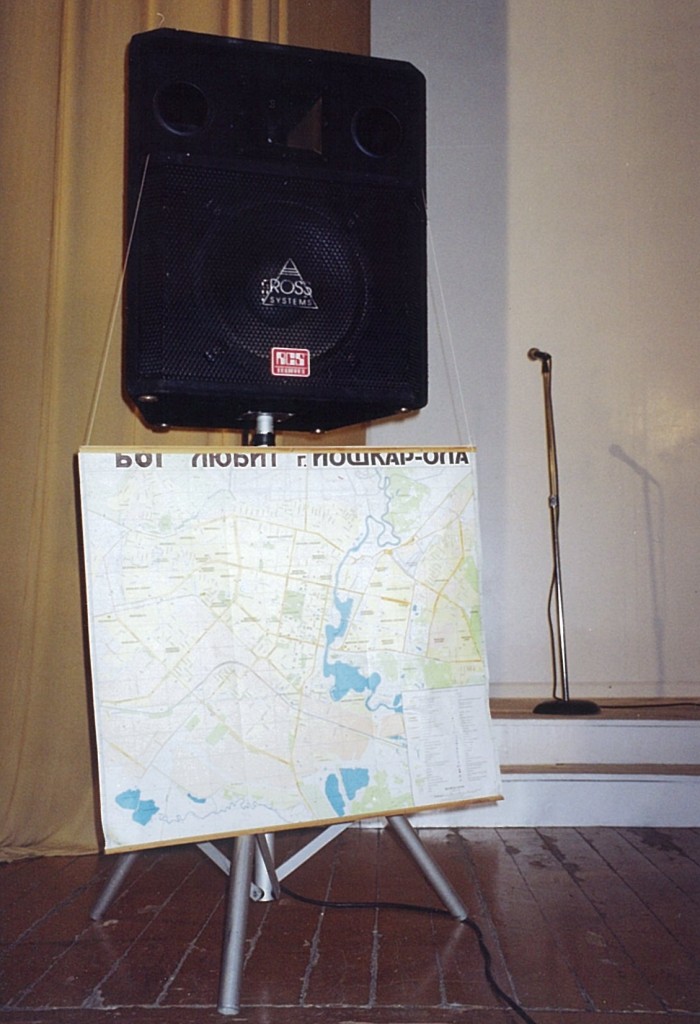

The photo above shows a map used for prayer by a Neo-Pentecostal Church in Ioshkar-Ola, Russia, where I did research in 2003-2008. The church met in a former cinema which had been purchased for them by the U.S.-based missionaries who had founded the church. At the time of my research, it was affiliated with the Embassy of the Blessed Kingdom of God for all Nations, a mega-church in Kiev led by a pastor of Nigerian origin. The material aspects of prayer at that church were interesting because, as good Calvin-inspired Protestants and as Charismatics committed to the spontaneity of the Holy Spirit, the pastor and congregation denied all significance of the material trappings of their church. At the same time, my observations and interviews with pastors, lay leaders, and members of the praise-and-worship band showed that they were keenly aware of the importance of material and performative preconditions for successful connections with the Holy Spirit. The result was a highly aestheticized style of worship whose practitioners denied and derided any importance of beauty, and an extensive use of material things with clearly “connective properties” that were nonetheless not to be considered holy.

One example is the prayer map: This map of the city in which the church was located was “just an ordinary map, bought in a store,” as church members assured me when I asked for permission to photograph it. The only thing that distinguished this copy from the one I had at home to find my way around the city was the computer-printed line “God loves the city of Ioshkar-Ola” that was glued across the top, and the frame that served for hanging it. It was, to borrow a term from Matthew Engelke, an “anti-object”: an object selected for maximal ordinariness and minimal likelihood of being taken for something special, but serving a function that cannot be dematerialized. During weekly prayers for the evangelization of the city, the map served very much as an interface between the pray-ers’ bodies and their desired effects on invisible spiritual realms: church members would stretch their arms toward the map and pray in tongues, waging spiritual warfare for their city’s deliverance from the devil. Though ordinary and store-bought, the anti-object (and anti-icon) was important enough to be one of two objects that the congregation moved to a makeshift worship space in the lobby during renovations of the main prayer hall. The other object was the loudspeaker, needed to amplify the sound of music and sermons.

Many of the objects in Anderson Blanton’s prayer portal are similar anti-objects, on whose ordinariness and lack of consecration most Pentecostals would insist as a condition for their practical usefulness in making sacred connections. Material supports for efficacious prayer are ubiquitous in the practice of these denominations, but denied by a theology that is suspicious of the idolatrous potential of material things. This creates an ethnographic and theoretical puzzle that forces the researcher to seriously engage theology while at the same time going against its grain. When we turn to Eastern Orthodox Christianity, however, the theological elaborations on the properties of holy things are so bountiful that an analysis that focuses on the material and the visual risks producing a mere translation of theology into the terms of actor-network theory. That step can be useful for shifting the overall image of Christianity in the still very Protestant-dominated Anglophone social sciences. But I think that part of the point of a social-scientific analysis of religious practices is always to produce a picture that’s a little different from that which a normative account of the religion would produce. The saints and theologians can say much better than we can how prayer is supposed to work from the inside of its practice. What we can add as social scientists is a framework that’s slightly shifted to include aspects that the devotee herself does not consider relevant.

A focus on the social embeddedness of interactions with holy things (the intersubjective preconditions of efficacious prayer) lies at the crossroads between theological elaborations of social hierarchy and mundane ways of thinking about kin, gender, and generation. It seems a promising way of bringing out the inherent ambiguities and open choices that accompany the commitment to canonically sanctioned orthopraxy in these diverse branches of Christianity. Between institutional hierarchies, connections of biological and spiritual kinship, and the shifting aesthetics of particular spaces or liturgies, there are many ways of “getting things right”. The ethnographic puzzle here might be how people negotiate that plurality while maintaining a commitment to a single unchanging standard of correctness.

Tags: Eastern Orthodox Christianity, materiality, Pentecostalism, Russia, theology