What does prayer sound, look, taste, and smell like? Can the person praying “feel” if the prayer is successful at establishing contact with a divine interlocutor, or do all prayers feel the same? The Eastern branches of Christianity have an especially rich sensory culture of prayer, including not only the famous icons and chants, but also the smell and warmth of oil lamps and incense, and the feel of book pages or prayer ropes between one’s fingertips. There are also media that allow a person to materialize a prayer without ever pronouncing it, such as a note on a crumpled piece of paper left in a wall, a prayer service recorded on a CD for home audition, a candle placed wordlessly in a church, or an invocation of a saint on a web forum.

What does prayer sound, look, taste, and smell like? Can the person praying “feel” if the prayer is successful at establishing contact with a divine interlocutor, or do all prayers feel the same? The Eastern branches of Christianity have an especially rich sensory culture of prayer, including not only the famous icons and chants, but also the smell and warmth of oil lamps and incense, and the feel of book pages or prayer ropes between one’s fingertips. There are also media that allow a person to materialize a prayer without ever pronouncing it, such as a note on a crumpled piece of paper left in a wall, a prayer service recorded on a CD for home audition, a candle placed wordlessly in a church, or an invocation of a saint on a web forum.

This prayer portal brings together materials from research in Egypt, the United States, Russia, Romania, and India to show a variety of sensory media used in those branches of Christianity with roots in the Hellenic and Aramaic-speaking parts of the Eastern Mediterranean. Though sharing a common set of sacred scriptures and a claim to succession from the early disciples of Christ, these branches are separated from Western Christendom by liturgical and aesthetic differences that predate the official schism between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches in 1054. However, they also display a great internal diversity and incorporate different political histories and traces of mutual influence with Catholic, Protestant, Muslim, and Hindu neighbors. Despite these obvious differences, we draw on materials from across the Eastern Christian world to point to liturgical forms, gestures, sounds, sights, and objects that resonate with one another and create an internally connected “aesthetic formation,” in Birgit Meyer’s term.

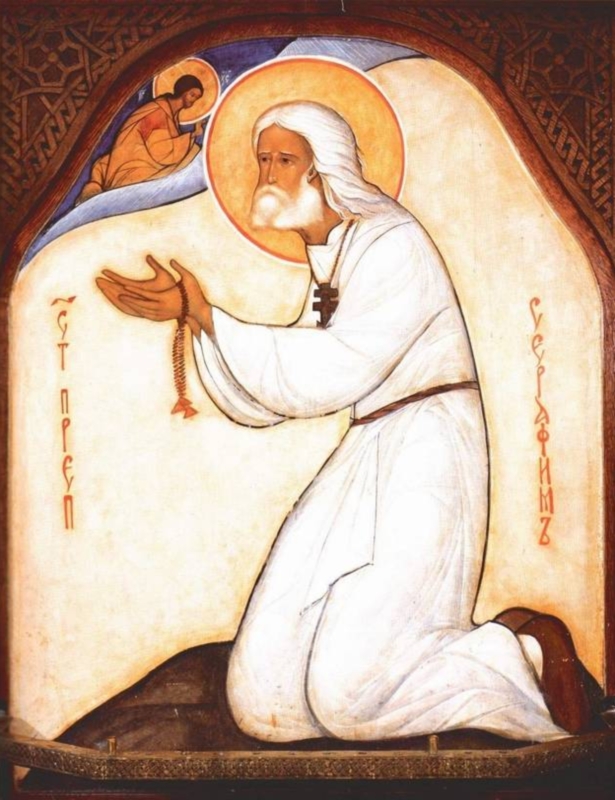

Some materials occur in different places: believers write requests on scraps of paper at the shrines of Saint Xenia in Saint Petersburg and Saint Abdel-Masih al-Manahri in Upper Egypt; relationships with confessors–known as “spiritual fathers”–shape the embodied practices and prayer texts in Romania and Russia; and akathist hymns dedicated to saints are popular in different countries as bridges between liturgical, collective prayer, and individual observances. A standard repertoire of gestures facilitates attentive listening and connects prayers in church and at home: standing or kneeling, crossing oneself, and bending down in prostrations. Although iconographic styles differ across times and places, there is a common idea that images mediate the real presence of saints and divine beings who are alive in the Church as a transhistorical community.

For the comparative study of prayer, these materials from Eastern Christianity suggest a number of possible lines of investigation: first, not all prayers are equal, and the efficacy of prayer depends on a number of factors. Some of them are internal to the praying person: his or her state of sincerity, undivided attention, preparation through fasting or prostrations, and knowledge of and access to prescribed prayer texts. Others are intersubjective: in a group of people praying together or in a situation where one person is interceding for others, there are social characteristics such as gender, age, clerical status, and training in recitation techniques that determine who recites a prayer and who listens, or whose duty it is to intercede for whom. The Russian proverb, “A mother’s prayer can fetch [her child] from the bottom of the ocean,” refers to one culturally accepted relation of intercession; the mutual, but differently empowered prayers of confessor and spiritual children are another. Finally, efficacy is also related to time and location: the distance travelled to the abode of a dead or living saint adds force and urgency to a prayer request, as does the capacity of a holy place to imbibe and become saturated with the many prayers said there over time. The beauty of a liturgy or the association of a particular saint or feast day with particular human problems can also help amplify a prayer request. All this raises questions about the possibilities and limits of thinking of prayer as a skill, and about the social, temporal, and spatial frameworks that are both essential to efficacious prayer and must continuously be broken up for prayer to reach beyond ordinary frames of existence.

Another fruitful comparative question could be that of creativity and inspiration in non-spontaneous prayer. Eastern Christians are rarely encouraged to pray “in their own words,” and certainly not “in tongues.” But prayer books often attribute texts to named saintly authors who are said to have been inspired by years of spiritual exercises. And even simple liturgical acts such as the reading of evening or morning prayers or the invocation of a saint in front of an icon are not straightforward acts of repetition, but require choices: how to combine specific formulae; whether to use an official prayer book or less regulated sources, such as small booklets or a text transmitted in a particular community; whether to perform that text completely or leave out elements; what tempo and style of recitation to adopt; how to time gestures with text and whether or not to use optional acts of physical exertion, such as prostrations. In looking at the generative possibilities of work within a pre-given tradition, the study of prayer can learn much from anthropological studies of ritual. But assumptions about how ritual persists and changes may also need to be adapted to the conditions of memory, transmission, and creativity in written religious traditions.

The entries in this prayer portal can be viewed in any order; each is organized around one or more images or recordings featuring a particular sensory medium of prayer or a set of sensory conditions that help prayer unfold its efficacy. Together, these materials show that in a religious tradition known as conservative and favoring collective over individual expression, everyday practice requires a great deal of creative combination of received elements to shape a multisensory whole.