The increasing burden on individuals to finance periods of heightened insecurity and risk out of their own pockets is at the very heart of what Jacob Hacker calls the increasing privatization of risk. But the increasing privatization of risk is but one part of a larger transformation in American society, albeit a very central part: the rise in inequality in economic well-being. As is well known by now, the difference in earnings between someone with a college degree and someone without one has grown substantially since the late 1970s. Perhaps less well known is the increasingly skewed distribution of wealth, in which returns from the stock market and other assets, such as real estate, flow disproportionately to those who have high incomes to begin with. Overall, as the economy has grown, the fruits of that growth have gone more to those in the top than in the middle and bottom of the economic ladder. 1

Because the resources that individuals have to fill in the gaps created by a fraying social safety net have become more unequally distributed, those on the lower rungs are less able to compensate for shortfalls in various forms of insurance coverage than those on the higher rungs. This is the best case scenario. At worst, those on the lower rungs have been subject to both lower earnings growth and greater erosion in benefits coverage. In either case, ever larger numbers of Americans face an environment in which a secure job, a healthy raise, and a sound benefits package seem elusive. 2

There is little disputing that the above changes have taken place—particularly the rise in income inequality and the streamlining of benefits—but there is contentious debate about their causes and consequences. Some see them as a necessary element of the restructuring of the American economy in order to make it more globally and technologically competitive. Others question the unequal nature of the restructuring, or the extent of the inequity, without questioning the need for restructuring itself. Few believe that a return to the old days is possible.

Where one touches down on these questions of the necessity and fairness of recent changes is crucial to answering the larger question of how the nation should respond to the new environment of heightened risk. Clearly experts are important players in this debate, and their views cover a wide range of territory, but the views of the public ought to matter as well. As Elisabeth Jacobs and Katherine Newman put it in their contribution to this forum, “[w]hile academics argue over whether ‘real’ insecurity has increased, Americans’ experience of their economic well-being remains a separate question.” While Jacobs and Newman focus on Americans’ changing perceptions of economic security, I focus on Americans’ changing perceptions of the fairness and necessity of inequality, which I argue captures the broader transformations of which increasing privatization of risk is a central part.

Inequality is Rising, but Don’t Americans Still Think Inequality is a Good Thing? 3

Before we consider Americans’ views of growing inequality, and all that it encompasses, we first have to understand their orientation toward inequality more generally. Here the distinction between inequality in principle and inequality in practice is a critical one. While Americans’ espouse principles of equality in the political realm (e.g., one man, one vote), they are less supportive of principles of complete equality in the economic realm. Indeed, economic inequality is viewed as fair because it rewards effort and talent, and it is viewed as necessary because it provides incentives for achievement and innovation, delivering greater prosperity to the entire society. As long as individual effort and talent are the only determinants of success, inequality in where people end up is considered just. 4

This much is pretty well known, but what is rarely appreciated is that Americans know that things are not that simple in practice. 5 And the case can be made that things have become a whole lot more complicated in recent decades. The lynchpins of Americans’ acceptance of inequality—“social mobility”and “equality of opportunity”—have always been slippery terms to get a hold of, particularly if we are talking about Americans’ perception of them. However, at least during the immediate postwar decades, many plausible indicators of social mobility moved in tandem, making the big picture easier to grasp. Jobs, incomes, and benefits all expanded together and were evenly distributed across the population, thanks to the existence of strong wage-equalizing institutions, such as wartime wage controls, unions, the minimum wage, equity norms in large corporations, and democratically-minded consumer movements. 6 The key exceptions were glaring—African Americans and women—but these exceptions were laid at the feet of a discriminatory society; they were not considered evidence of an inherently disequalizing economy.

The picture since the 1980s is considerably more complex. Unlike the 1940s through the 1970s, jobs and income growth diverged and an expanding economy no longer promised growing incomes for everyone, let alone equal growth in incomes. Until the late 1990s, employment grew but was slow by postwar standards and earnings fell or stagnated for the majority of men and a considerable minority of women. Minorities and women were more formally incorporated into the economy, but discrimination continued, inequality within these groups increased, and there was essentially no reduction in poverty from the 1970s to the late 1990s. The economic boom of the late 1990s did indeed lift all boats but it did so unevenly—fantastically for some and modestly for others—leaving intact the high overall level of inequality that had been built up over the 1980s and early 1990s, to levels not seen since before World War II. 7

Adding to this complexity, large American corporations have gone through many phases of restructuring that have had a disparate impact on different groups of workers, and at different points over time. 8 Massive blue collar layoffs characterized the early 1980s recessions, whereas white collar workers became more vulnerable to layoffs thereafter, and especially during the early 1990s recession and the downsizing wave of the mid-1990s. The new emphasis on stock market earnings as the definitive measure of corporate performance in the 1980s made executives tenure more tenuous but also more lucrative, spawning the great increase in executive compensation that made headlines especially in the early 1990s (more on this later). And then of course there was the big, and completely unexpected, stock market and technology boom of the late 1990s. Thus the good was mixed with the bad, and sorting out one from the other has been a challenge for the expert as well as the lay person.

Did any of this shake Americans’ confidence in the possibility of upward mobility, the lynchpin of their principled acceptance of inequality? Given the wide range of divergent changes that has taken place, which, if any, are the most closely tied to Americans’ views of the fairness and necessity of inequality in practice as opposed to in principle?

Perceptions of the Necessity and Fairness of Inequality in Practice

Americans are disapproving of the amount of inequality in practice but the degree of disapproval seems to depend on two factors: real economic growth and a belief that economic growth is equitable, that is, that all boats are lifted when the economy grows. Now it may seem that these are virtually the same thing, but in fact they are not, precisely because the postwar pattern of equitable growth—that all boats were lifted equally—ended in the 1970s without a big newsflash. Academics and experts hardly knew about it until the late 1980s and early 1990s. As a social fact (rather than an economic reality), rising inequality is not only a more recent phenomenon than many think but a relatively difficult one to perceive.

In this new environment, it is harder to assess whether opportunities for upward mobility are still open or are being thwarted, especially if Americans continue to assume, in a kind of historical lag, that all growth is equitable growth. What is needed is a way to look beyond an array of truly positive economic developments—low unemployment, a strong stock and housing market, technological competitiveness, to name a few—to the question of whether economic opportunity is nevertheless unfairly limited. Because it is possible that Americans would accept some degree of unfairness if they think it is necessary to maintain overall growth, economic conditions that seem unnecessary as well as unfair are the most likely to unsettle Americans’ faith in the American Dream.

This is precisely where the privatization of risk, and many other crucial elements of the overall rise in inequality, come into play. The increasing privatization of risk is a concrete example of inequity in practice. This matters because social scientists have long known that the term “inequality” itself is a very ill-defined and abstract one, especially when referring to income inequality, as opposed to racial or gender inequality, which at least involve differences between relatively clearly defined social groups (i.e., men and women, blacks and whites, etc.). As a result of the difficulty of mapping income onto real social groups, researchers do not use the term inequality in survey questions but instead ask about “differences in income” between “the rich and the poor” or “the haves and the have-nots,” and so on. While an improvement, even these are imprecise and open to a wide variety of interpretations.

In contrast, inequality-related issues that are either more accessible or more directly connected to the everyday experiences of individuals—failing pension and health plans for the middle class while executives enjoy premium coverage and stock market windfalls that can secure them in the event of a catastrophic illness, a temporary bout of unemployment, or old age—can better communicate the message of inequitable economic growth. But the issue must be linked to a framework of inequality, in which a few are gaining while the majority is losing out, in order for it to be deemed both unfair and unnecessary. Otherwise, if everyone is subject to the same cutbacks, then a little belt-tightening for everyone can be seen as a necessary and shared sacrifice on the road to greater prosperity.

Two issues that I have investigated meet these requirements (of being perceived as unfair and unnecessary). One, downsizing, is an aspect of the increasing insecurity, instability, and “risk” of employment. 9 It alludes to mass layoffs of blue and white collar workers during periods of economic expansion and healthy profit growth, thus throwing up images of unequal outcomes (i.e., the juxtaposition of layoffs and profits). Downsizing as such began in the 1980s but came to prominence in the mid-1990s. The other issue, excessive executive pay, is an accessible and self-explanatory example of inequality in practice. It too became prominent in the 1990s. I tracked media coverage of both issues to help understand fluctuations in support for inequality that did not correspond exactly to fluctuations in the common and official indicators of economic growth, such as output and employment growth. It therefore could not be economic growth alone that mattered; perceptions of whether economic growth was equitable must come into play as well.

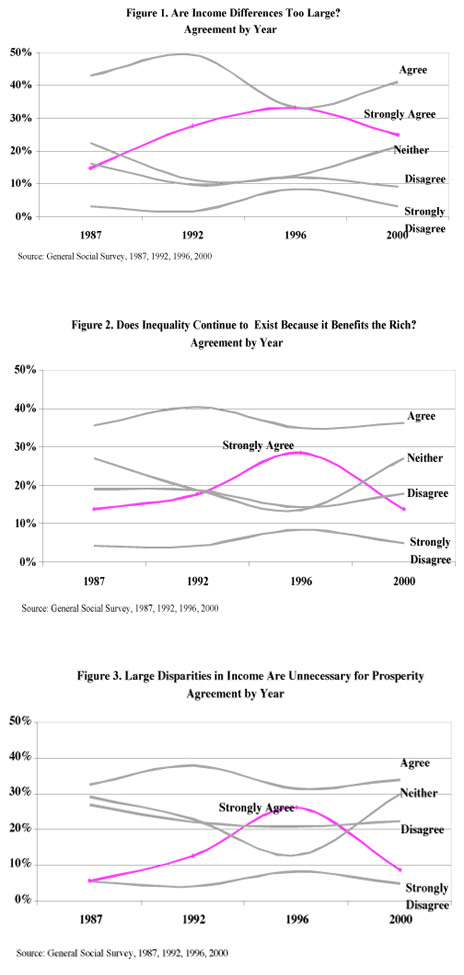

The relationship between economic growth and support for inequality can be seen in Figures 1, 2, and 3 for four time points: 1987, 1992, 1996, and 2000 (unfortunately these same questions have not been replicated in more recent years). Each figure charts responses to a question that is meant to capture a different aspect of inequality, such as its fairness or necessity. The first question is a straightforward indicator of how much inequality in practice is tolerated by Americans; it asks simply whether “differences in income are too large.” The second question asks about the fairness of inequality, specifically whether “inequality continues to exist because it benefits the rich.” This question, I would suggest, taps into the notion of the “undeserving rich,” a term that has not been used in recent times but bears a resemblance to the “idle rich” of earlier periods. It is also analogous to the much more common notion of the undeserving poor (i.e., the poor lack a work ethic and therefore do not deserve government hand outs). Finally, the third question asks about the functionality or necessity of inequality for growth, specifically whether “large disparities in income are necessary for America’s prosperity.”

Contrary to the popular perception that Americans accept inequality in practice, and that this acceptance is unflinching, Americans express considerable opposition to all three aspects of inequality, as well as variation in opposition over time. Agreement that income differences are too large ranges from a low of 58.0 percent in 1987 to a high of 77.1 in 1992 (combining those who agree and strongly agree). The numbers are lower but still substantial for the other two questions: agreement that inequality continues to exist because it benefits the rich ranges from a low of 49.4 percent in 1987 to a high of 63.4 in 1996, and agreement that large disparities in income are unnecessary for prosperity ranges from a low of 38.2 percent in 1987 to a high of 57.9 in 1996.

For two of the three questions, total agreement peaks in 1996, but for all three questions strong agreement peaks in 1996, which was neither a peak nor a trough in the business cycle over this period. In fact, if one were to look at the formal indicators of economic growth—the unemployment rate and the growth rates of GDP and productivity—you would find that the economy was in slightly better shape in 1996 than it was in 1987, yet 1987 is the low point in the range of opposition to inequality for all three questions. The next lowest point of opposition was in the year 2000, the peak of the strongest run of economic growth since the 1960s, as one might expect. Economic growth and decline is therefore an important indicator of opportunity, as evidenced by the high degree of opposition to inequality during the recessionary period of 1992 and low degree of opposition during the expansionary periods of 1987 and 1992, but it is not the entire story.

One reason growth alone is not the whole story is because Americans are also concerned about equitable growth. Since equitable economic growth is not as readily apparent as growth alone—or is assumed to accompany growth until proven otherwise—there may be an uneven mapping of perceptions of in/equitable growth onto actual in/equitable growth. This is due at least in part to the fact that the media covers unemployment figures and other business cycle indicators obsessively but does not do the same for inequality figures.

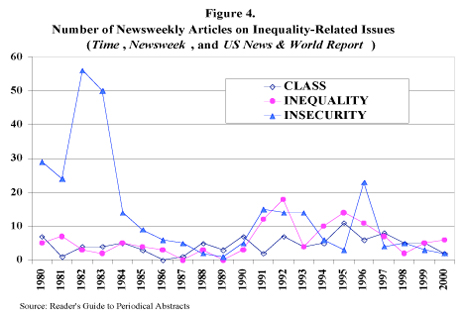

As shown in Figure 4, the media’s coverage of a wide range of issues related to insecurity, inequality, and class tracks the business cycle in part but not in total. Coverage of unemployment (under the heading of “insecurity”) peaked dramatically around the time of the early 1980s recession, but the next highest peak was not during the early 1990s recession but during the recovery in 1996. Most of these stories were about downsizing, which we also categorized under the heading of “insecurity.” Surprisingly, in 1992, we actually see more stories on inequality than on insecurity, and then the focus on inequality continues into the mid-1990s. In 1992, excessive executive pay was a prominent type of inequality-related story, and in 1995 the emphasis shifted to a more general discussion of the growing gap between the rich and the middle class. In short, the sum total of stories on insecurity, inequality, and class has three clearly defined peaks in 1982-1984, 1992, and 1996, mirroring the peaks in opposition to inequality shown above.

By the end of the 1990s, coverage of insecurity, inequality, and class had all but disappeared. If the earlier periods of inequitable growth, and coverage of inequitable growth, seem to track opposition to inequality fairly well, what does the late 1990s period tell us about Americans’ support for inequality? The late 1990s boom was in fact a boom of the “lift all boats” variety, and media coverage did nothing to contradict this fact. However, all boats were not lifted equally; some forms of inequality were reduced but the overall level inequality remained at historic levels. Americans were either unaware of the uneven nature of the late 1990s boom, and the persistently high levels of inequality, or they were genuinely unconcerned about them as long as they perceived (correctly) that everyone gained. Unfortunately, we cannot distinguish between these two possibilities. It is certainly conceivable that a “lifting of all boats, even if unevenly” counts as equitable growth for many Americans.

In sum, Americans care about unfair and unnecessary forms of inequality because they see these as barriers to social mobility. But such barriers are not terribly transparent. And they are arguably less transparent now than they used to be in the prosperous decades following World War II when all growth was equitable growth and the blatant exceptions were attributed to discrimination rather than an inherently disequalizing economy. Since the 1970s, equity and growth have become decoupled, and African Americans, other racial and ethnic minorities, and women have made formal as well as substantive progress, even though much discrimination continues to exist. In this new environment, it is intrinsically more difficult to identify the workings of inequality in practice, particularly if Americans’ assumption that all growth is equitable growth persists. Because Americans’ faith in their own prospects for upward mobility is so firmly embedded in the dynamism of the American economy, they might accept cutbacks in benefits if they are deemed necessary to maintain growth and competitiveness. It is therefore critical that such cutbacks be seen not as a shared sacrifice but as an unfair burden on the majority of working families while the “undeserving rich” are spared, or even further enriched by the process.

The Politics of Inequality and the Privatization of Risk

So far I have said little about why Americans’ perceptions of inequality in practice matter for how problems such as the increasing privatization of risk are addressed. I think the answer is a fairly simple (and perhaps naïve) one: that public recognition of the increasing privatization of risk as a social problem is an important component of the political process of reform. Revealing inequities in the distribution of risk is one way to raise concern about it, and the unequal distribution of risk in turn can serve as an accessible example of the broader rise in inequality, an abstract and often complicated topic that otherwise receives little direct attention.

It is also essential that the public’s views on inequality-related issues be known apart from their views on inequality-related policies, for lack of support for the latter is often taken erroneously as lack of concern for the former. For example, we often conclude that a lack of support for welfare implies a lack of concern for poverty, which is not the case. 10 Focusing directly on the public’s views of inequality-related issues is a way to keep our apples (concern for inequality) separate from our oranges (possibilities for public policy reform).

Having established this separation, however, what can be said about the connection between Americans’ concern for inequality and their support for inequality-reducing public policies? Although a complete answer would take up the space of another full essay, the short (and preliminary) answer is that the connections appear to be very weak. Indeed, part of what makes the pattern of opposition to inequality in the 1990s credible is that it goes against the grain of a general shift toward policy conservatism during the 1990s, evident most obviously in the elimination of welfare as an entitlement program during the same period in which opposition to inequality was at its highest in 1996.

In addition, according to the same survey that asked about Americans’ attitudes toward inequality (reported above), support for a broad range of policies—including taxes, spending on health, and assistance to the poor—was not significantly higher in 1996. The one exception is spending on education, which was slightly higher in 1996 and 2000. That Americans draw a connection between inequitable barriers to social mobility and educational reform is not surprising (and the correlations between the two increased in 1996), particularly given the ubiquitous message that a college education is required if one is to succeed in the new economy. Apart from education, then, traditional social policies (or at least those asked about in survey questionnaires) offer little hope for the large segment of Americans who are concerned about the level of inequality in American society.

The disconnection between Americans’ views of inequality and the social policies that are meant to mitigate inequality is not surprising given than social protections were delivered through a strong postwar economy rather than a strong postwar state, as was more typically the case in war torn Europe. But what made the strong postwar economy an equitable postwar economy were the equalizing influences of the war, the New Deal, unions, democratically-minded consumer movements, and equity norms in large corporations. 11 Without these influences today, Americans place all of their eggs in the one basket of education.

In closing, one promising avenue for further exploration was suggested by the question about whether “inequality continues to exist because it benefits the rich.” In this era of corporate scandals on the one hand and post-welfare-reform on the other, when the poor are not as heavily demonized or scapegoated as they used to be, and the rich are out of favor, it may be time for a new frame—the “undeserving rich”—to claim the space once occupied by the “undeserving poor.” The potential political differences between the two frames is striking: whereas the “undeserving poor” served to limit social policy reform, the “undeserving rich” has the potential to resuscitate it, as long as it is tightly hitched to those aspects of inequality that are deemed both unfair and unnecessary. This is easier said than done, since Americans generally do not endorse limitations on the earnings of the rich, though they do think executives are overpaid. 12 It seems that a more promising route—for which there seems to be considerable public support 13—is to better regulate the kinds of corporate abuses that have given executives a bad name and left many Americans with less secure jobs, pensions, and health care.

- For an accessible review of the economic patterns described in this essay, see David Ellwood, “Winners and Losers in America: Taking the Measure of the New Economic Realities,” in D. Ellwood et al., A Working Nation: Workers, Work, and Government in the New Economy (Russell Sage Foundation, 2000). For a longer historical period, see Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, “Income Inequality in the United States: 1911-1998,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 2003, CXVII:1-39, and Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz,“Decreasing (and then Increasing) Inequality in America: A Tale of Two Half-Centuries,” in F. Welch, eds., The Causes and Consequences of Increasing Inequality (University of Chicago Press, 2001). ↩

- Neil Fligstein and Taek-jin Shin, “The Shareholder Value Society: Changes in Working Conditions and Inequality in the U.S., 1975-2000,” in K. M. Neckerman, ed., Social Inequality (Russell Sage Foundation, 2004). ↩

- For further details on the following argument and analysis, see Leslie McCall, “Do They Know and Do They Care? Americans’ Awareness of Rising Inequality,” Working Paper, Russell Sage Foundation, 2005. ↩

- Jennifer Hochschild, What’s Fair? American Beliefs about Distributive Justice (Harvard University Press, 1981) and Facing Up to the American Dream: Race, Class and the Soul of the Nation (Princeton University Press, 1995). ↩

- James Kleugel and Elliot Smith, Beliefs About Inequality: Americans’ Views about What Is and What Ought To Be (De Gruyter, 1986). ↩

- Although I do not have the space to discuss it here, the private economy-based equitable growth that I describe must be seen as a historically specific outcome of the political failure to extend the New Deal at war’s end, thus providing the impetus to seek greater equity in the private-sector institutions of mass consumption and production. See Steve Fraser and Gary Gerstle, eds., The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order (Princeton University Press, 1990), Lisabeth Cohen, A Consumer’s Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America (Vintage, 2004). For comparisons with Europe in the immediate postwar period, see Susan Strasser, Charles McGovern, and Matthias Judt, eds., Getting and Spending: European and American Consumer Society in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge University Press, 1998). ↩

- Lawrence Mishel, Jared Bernstein, and Heather Boushey, The State of Working America, 2002/2003 (Cornell University Press, 2003), and Edward Wolff, Top Heavy: The Increasing Inequality of Wealth in American and What Can Be Done About It (The New Press, 2002). ↩

- For an accessible review of this literature, see Leslie McCall, The Inequality Economy: How New Corporate Practices Redistribute Income to the Top, Working Paper, Demos: A Network for Ideas and Action, 2004. ↩

- Unfortunately, I have not tracked coverage of health and pension-related inequalities. ↩

- Martin Gilens, Why Americans Hate Welfare: Race, Media, and the Politics of Antipoverty Policy (University of Chicago Press, 1999). ↩

- Again, I do not wish to minimize the political nature of these developments. See endnote 6. ↩

- Kluegal and Smith (1986). ↩

- Stanley Greenberg and Anna Greenberg, “Taxes, Government, and the Obligations of Citizenship,” Greenberg, Quinlan, and Rosner Research, Inc., 2003. ↩