[Editor’s Note: This post is in response to “Praying with the Senses,” Sonja Luehrmann’s portal into Reverberations’ unfolding compendium of resources related to the study of prayer.]

I heartily welcome Reverberations’s new prayer portal, “Praying With The Senses,” as it not only tackles significant issues in the study of prayer from a variety of methodological angles, but it also brings much needed attention to that which continues to be a significant lacuna in religious studies—namely, the distinctive characteristics of various expressions of Eastern Christian faith and practice.

I heartily welcome Reverberations’s new prayer portal, “Praying With The Senses,” as it not only tackles significant issues in the study of prayer from a variety of methodological angles, but it also brings much needed attention to that which continues to be a significant lacuna in religious studies—namely, the distinctive characteristics of various expressions of Eastern Christian faith and practice.

Sonja Luehrmann’s curatorial introduction highlights a number of the distinctive factors that affect “the efficacy of prayer” in Eastern Christianity. Many of these factors reveal how the Eastern Christian traditions are fraught with tension between formal regulations prescribed by ecclesiastical authority and the ambiguities and “judgment calls” that confront the individual believer in actual practice. As Luehrmann puts it, some of these factors

are internal to the praying person: his or her state of sincerity, undivided attention, preparation through fasting or prostrations, and knowledge of and access to prescribed prayer texts. Others are intersubjective: in a group of people praying together or in a situation where one person is interceding for others, there are social characteristics such as gender, age, clerical status, and training in recitation techniques that determine who recites a prayer and who listens, or whose duty it is to intercede for whom.

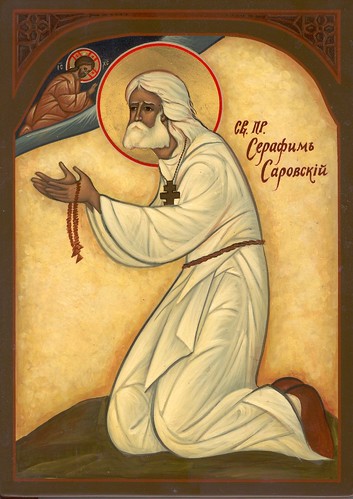

I will here focus on the last aspect of intersubjectivity that Luehrmann observes, especially as it is manifested in Daria Dubovka’s entry, “Spiritual Fathers and Spiritual Children.” In much of Eastern Christianity, there are standard understandings of “whose duty it is to intercede for whom.” A saint’s prayers, for example, are more coveted than a clergyman’s. A clergyman’s prayers are more coveted than a layperson’s. Such regulations would seem to eradicate ambiguity about whose prayers are to be sought and for what reason.

However, Dubovka’s exploration of the value that Orthodox Christian believers place on the intercessory prayers of a “spiritual father” (sometimes referred to as a staretz) reveals how the individual believer is often faced with situations that require exercising one’s own convictions concerning whose intercessory prayers are most worthy of being sought. As Dubovka observes, there is a “complex social relationship implied in intercession” in which “believers ask God to strengthen the prayers of their spiritual father, but also acknowledge that God hears them only thanks to his prayerful support.” That is, because the spiritual father is discerned to be a “living saint,” his prayers carry an extraordinary power. At the same time, however, the spiritual father’s holiness (which augments the power of his prayers) is itself bolstered and enhanced by the intercessions of those who trust in his spiritual fatherhood.

This paradox is augmented further upon the death of a spiritual father. Those who remain in this life have the duty to assist the dearly departed one in the journey towards paradise through their intercessory prayers. These prayers are prescribed to be carried out in a formal liturgical manner for 40 days after an Orthodox Christian’s death. At the same time, a devotee of the spiritual father who is personally convinced of the spiritual father’s saintliness often begins to seek his intercessions prior to any official canonization of sainthood by formal ecclesiastical bodies. Indeed, such official canonization often only comes about if those who have sought the departed one’s intercessions can make compelling claims that these intercessions have wrought miracles. The saint, then, is recognized as a saint through demonstrating the power of his prayers, while this demonstration is made possible only because: 1) the community of those who believe in his sanctity have themselves assisted him through their intercessions after his death; and 2) this same community has sought continual encounter with his sanctity even after he is no longer physically present in this world.

As a result, individual Orthodox Christian believers (and the local community that they constitute) must follow their own personal convictions concerning the value of seeking the departed one’s prayers apart from any official sanction from the hierarchy of the Orthodox Church. Doing so requires an act of courage not only because the believer does not yet have the backing of ecclesial authority, but also because quite often there are other members of the community who do not share the same high estimation of the departed. Considerable controversy and pain can result in these situations, as some Orthodox faithful are seeking intercessory prayers from the same individual that others regard, in the more extreme scenarios, as a complete fraud. Fyodor Dostoevsky dramatizes a particularly vivid example of this tension in a critical passage from The Brothers Karamazov. When Alyosha Karamazov’s beloved spiritual father, the Elder Zosima, dies, it becomes an opportunity for Zosima’s opponents to challenge his holiness and argue that he was a charlatan who had led many astray. Alyosha, convinced of Zosima’s sanctity, is thrown into a personal crisis until he resolves to pursue his convictions in the face of opposition. His resolve in the face of such opposition leads to Alyosha experiencing a vision of his dearly departed Elder, who continues to spiritually advise him. His relationship with Zosima and his belief in his intercessory prayers thus continues after Zosima’s death, despite stiff opposition from many others in the local community.

This is not merely a literary phenomenon. In the contemporary American Orthodox parishes in which I have been a worshipping member and ordained minister, I have regularly witnessed these difficult ambiguities play themselves out. Regardless of whether a person is a cleric or a layperson, and regardless of whether he or she is generally regarded as saintly, “an average joe,” or a downright unholy, the community prays for him or her for 40 days. During these 40 days, however, one will inevitably begin to encounter individual members of the parish who have already begun to seek the recently departed one’s intercessory prayers, and even to assert that they have directly experienced these prayers’ efficacy. Such efficacy may range from an experience of emotional consolation to improbable phenomena that are believed to be miracles wrought by intercessory prayer.

Perhaps most striking, then, is that while the Eastern Orthodox Church has a liturgical calendar in which it recognizes a delimited number of “official” saints, there are innumerable “unofficial” saints whose intercessions believers seek—and the efficacy of which believers experience—without the confirmation of ecclesial authorities.

Tags: canonization, intercession, saints, spiritual father, staretz