“Crying Holy Unto the Lord” became a staple of the bluegrass circuit and was sung by the likes of Bill Monroe and Flatt & Scruggs. Here we have Waters standing on the rock of Moses, crying out, subjunctively, and establishing an intimate relationship to the father and the son. She seeks intimacy and she achieves it to the degree that she is capable of communicating with sinners. Missionizing to and toying with, Waters gets her message across.

In the last lines, we have Waters riffing over the infectious rhythm and offering an object lesson to those who seek to escape the conditions of their shared being. She encourages sinners to run to the rock and hide their faces, all for the purpose of revealing to them that there is no hiding place after all.

You should have known this from the beginning.

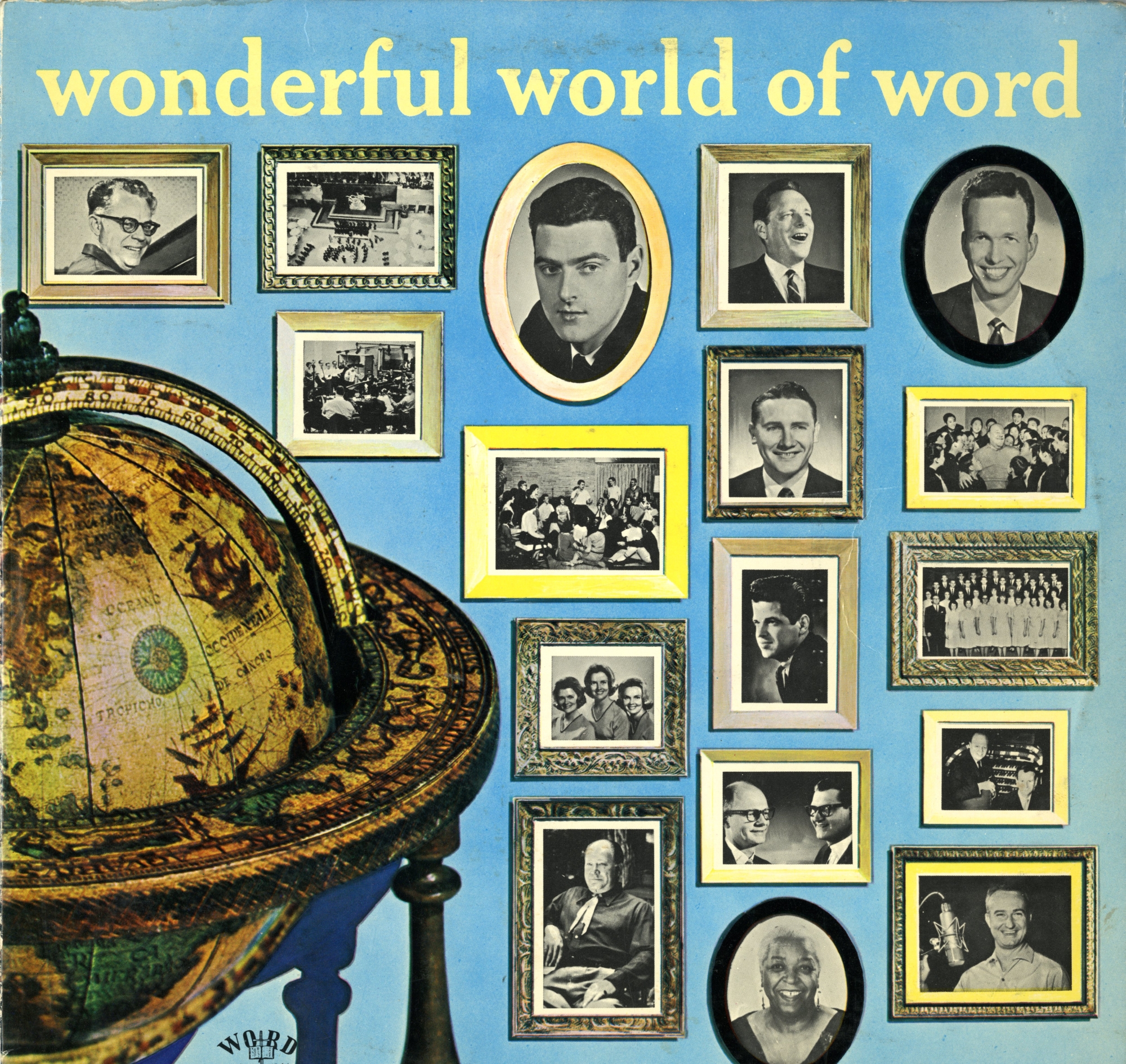

In the liner notes of the Wonderful World of Word compilation, the language of universalism is intense: past, present, and future fold in upon one another; sound waves emanating outward, from the recording studio “through a network of channels that not only crisscross North America but extend to the ‘Land Down Under,’ to the icy slopes of Greenland and on to all the seven continents.”

The world of WORD records out of Waco, Texas is “ever expanding” and spans the spectrum of Sacred sound. It moves from the Old Masters to today’s contemporary composers. It progresses from the greats of yesterday to those on the threshold of prominence tomorrow. It encompasses nearly every musical instrument in existence, from the solo human voice to the versatile piano and organ (both pipe and electronic), to each individual instrument of the families of string, brass, woodwinds, and percussion. It takes in, via recording, a repertoire that includes nearly every song in every hymnal in use today by the Church. The selections range from those penned by Martin Luther and his associates to the works of the still unknown, but outstanding writers of the day. The moods that are projected through this music run the gamut of human emotions. The overshadowing, underlying and penetrating purpose of every record is to communicate the Christian message.

The use of “nearly” undermines the universalism, however, suggesting the limits of, among other things, racial codings of pious whiteness.

The theological limits are marked by more mundane signs. Ethel Waters, an accomplished blues and Broadway singer, is the only African-American artist to appear on the compilation. The first song—“Sunlight” by the White Sisters—suggests an epistemology grounded in the illumination that emanates from a white hot center of Protestant presence.

Sabotage is integral, here, to Waters’ use of the “radio-phonograph.” She is like the narrator of Ellison’s Invisible Man, listening to and feeling the vibration of Louis Armstrong’s “What Did I Do to Be so Black and Blue.” And Waters is the vibration as well.

Perhaps I like Louis Armstrong because he’s made poetry out of being invisible. I think it must be because he’s unaware that he is invisible. And my own grasp of invisibility aids me to understand his music. Once when I asked for a cigarette, some jokers gave me a reefer, which I lighted when I got home and sat listening to my phonograph. It was a strange evening. Invisibility, let me explain, gives one a slightly different sense of time, you’re never quite on the beat. Sometimes you’re ahead and sometimes behind. Instead of the swift and imperceptible flowing of time, you are aware of its nodes, those points where time stands still or from which it leaps ahead. And you slip into the breaks and look around. That’s what you hear vaguely in Louis’ music. (Invisible Man, 7-8)

For Ellison’s invisible man, listening to Armstrong is apocalyptic—a hermeneutical revelation that gives immediate substance to the way he has chosen to see and interpret the world. “Under the spell of the reefer,” he writes, “I discovered a new analytical way of listening to music. The unheard sounds came through . . . That night I found myself hearing not only in time, but in space as well. I not only entered the music but descended, like Dante, into its depths” (8-9). Not only has this immersion given him hope that there were, in fact, fissures and openings within linear conceptions of time that undergirded the ideology of whiteness, it has strengthened his resolve to inhabit these in-between spaces.

Within these spaces, you are free to recover that which has been denied a formal hearing, to change your mind, and to imagine a different future.

Tags: evangelical secularism, Ralph Ellison, reefer, The White Sisters, universalism, WORD Records