Partly in response to the prayer portal on “Praying with the senses,” Anderson Blanton and Sarah Riccardi and Aaron Sokoll have started an interesting discussion of how to theorize the role of material objects as “media for connectivity” (Riccardi and Sokoll) orr a bodily “interface” (Blanton) for prayer. I agree with most of what the three authors say, but would like to use an example from previous research on Pentecostal Christians in Russia to explain what is pushing me away from making the connective properties of sacred objects the sole focus of our exploration of the sensory workings of Eastern Christian prayer. In short, I think that the “wow-effect” that an emphasis on materiality brings to studies of Pentecostalism and other branches of Protestant Christianity isn’t there for Eastern Orthodoxy, where, as Riccardi and Sokoll point out, the significance of the material holy goes “back to key councils and writings of … saints and theologians.”

Partly in response to the prayer portal on “Praying with the senses,” Anderson Blanton and Sarah Riccardi and Aaron Sokoll have started an interesting discussion of how to theorize the role of material objects as “media for connectivity” (Riccardi and Sokoll) orr a bodily “interface” (Blanton) for prayer. I agree with most of what the three authors say, but would like to use an example from previous research on Pentecostal Christians in Russia to explain what is pushing me away from making the connective properties of sacred objects the sole focus of our exploration of the sensory workings of Eastern Christian prayer. In short, I think that the “wow-effect” that an emphasis on materiality brings to studies of Pentecostalism and other branches of Protestant Christianity isn’t there for Eastern Orthodoxy, where, as Riccardi and Sokoll point out, the significance of the material holy goes “back to key councils and writings of … saints and theologians.”

Sonja Luehrmann

Sonja Luehrmann received her Ph.D. in anthropology and history from the University of Michigan—Ann Arbor, in 2009, and is Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Simon Fraser University. Her research has focused on Orthodox Christian encounters with other religious and ideological traditions in such multi-ethnic settings as the Soviet and post-Soviet Middle Volga region and nineteenth-century Alaska. She is currently engaged in an IREX-funded ethnographic project on anti-abortion activism and regimes of penance in the Russian Orthodox Church, and completing a book manuscript on the epistemological and methodological challenges of looking at religious practices through the militantly secularist lens of socialist state archives. Dr. Luehrmann’s publications include Secularism Soviet Style: Teaching Atheism and Religion in a Volga Republic (Indiana University Press, 2011) and Alutiiq Villages under Russian and U.S. Rule (University of Alaska Press, 2008).

Posts by Sonja Luehrmann

September 4, 2013

A Letter from Mr. and Mrs. Historian

Dear Ms. Social-Cultural, dear Mr. Cognitive:

Dear Ms. Social-Cultural, dear Mr. Cognitive:

We were intrigued to learn about your quarrel, and it reminded us of arguments we’ve had since we got involved in a new pursuit called the “History of Emotions.” We have both become quite passionate about studying the fine art of blushing in Victorian Britain or the question whether or not Native Americans on their vision quests felt as abject as the texts of their songs suggest, or if the songs were just to make the spirits pity them. We love finding texts and images in archives and libraries and inferring structures of feeling from them.

June 17, 2013

Praying with the Senses: A Curatorial Introduction

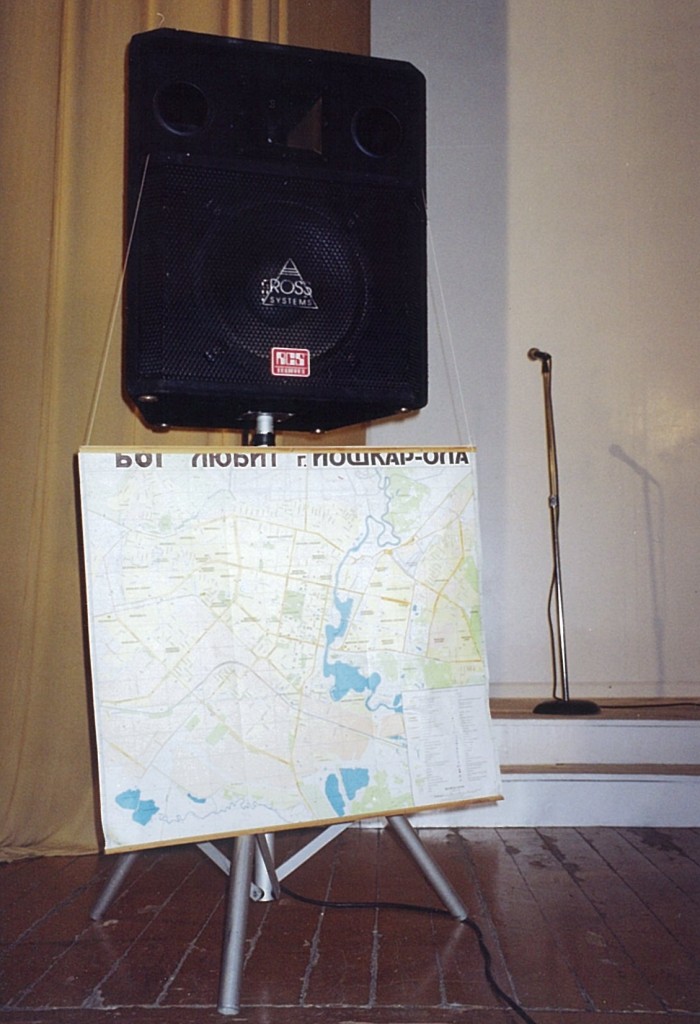

What does prayer sound, look, taste, and smell like? Can the person praying “feel” if the prayer is successful at establishing contact with a divine interlocutor, or do all prayers feel the same? The Eastern branches of Christianity have an especially rich sensory culture of prayer, including not only the famous icons and chants, but also the smell and warmth of oil lamps and incense, and the feel of book pages or prayer ropes between one’s fingertips. There are also media that allow a person to materialize a prayer without ever pronouncing it, such as a note on a crumbled piece of paper left in a wall, a prayer service recorded on a CD for home audition, a candle placed wordlessly in a church, or an invocation of a saint on a web forum.

What does prayer sound, look, taste, and smell like? Can the person praying “feel” if the prayer is successful at establishing contact with a divine interlocutor, or do all prayers feel the same? The Eastern branches of Christianity have an especially rich sensory culture of prayer, including not only the famous icons and chants, but also the smell and warmth of oil lamps and incense, and the feel of book pages or prayer ropes between one’s fingertips. There are also media that allow a person to materialize a prayer without ever pronouncing it, such as a note on a crumbled piece of paper left in a wall, a prayer service recorded on a CD for home audition, a candle placed wordlessly in a church, or an invocation of a saint on a web forum.

June 17, 2013

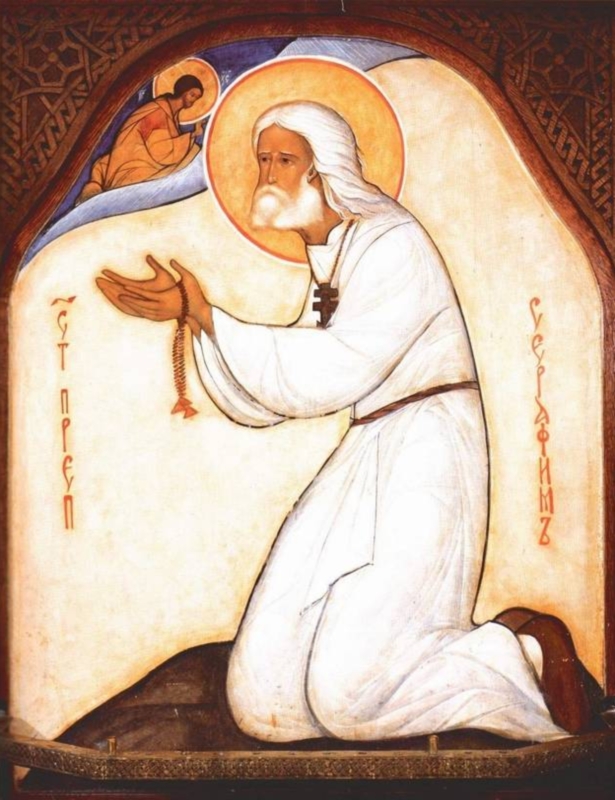

Restraint and Outpour: Emotions Across Genres of Prayer

When distinguishing religious from secular activity, contemporary Russian Orthodox believers often draw a contrast between the spiritual and the sensuous. Coming from Byzantine monastic writings that were popularized by nineteenth-century Russian clerics, this contrast refers to two different modes of human existence. Prayer and participation in liturgy are intended to develop the spiritual potential of the human being, moving beyond mere emotion or esthetic enjoyment. Key characteristics that make churches a spiritual space removed from secular sensuality are iconographic styles that depict saints as timeless, serene beings of no particular age, existing in eternity rather than historical time; and liturgical chants that are performed a cappella, in rhythms that are often governed by the words that are sung. The canonical texts of services and hymns to saints also often shy away from the more gory details of their lives and sufferings, to focus on them as spiritual exemplars. But especially when it comes to more popular and lay-oriented forms of praise and prayer, the elements of a liturgical setting can pull in different emotional directions.

When distinguishing religious from secular activity, contemporary Russian Orthodox believers often draw a contrast between the spiritual and the sensuous. Coming from Byzantine monastic writings that were popularized by nineteenth-century Russian clerics, this contrast refers to two different modes of human existence. Prayer and participation in liturgy are intended to develop the spiritual potential of the human being, moving beyond mere emotion or esthetic enjoyment. Key characteristics that make churches a spiritual space removed from secular sensuality are iconographic styles that depict saints as timeless, serene beings of no particular age, existing in eternity rather than historical time; and liturgical chants that are performed a cappella, in rhythms that are often governed by the words that are sung. The canonical texts of services and hymns to saints also often shy away from the more gory details of their lives and sufferings, to focus on them as spiritual exemplars. But especially when it comes to more popular and lay-oriented forms of praise and prayer, the elements of a liturgical setting can pull in different emotional directions.

February 26, 2013

Sensory Spirituality: Prayer as Transformative Practice in Eastern Christianity

What does it take to pray well, and how does a regular practice of prayer help remake the devotee into a person who has this ability? Our research team asks how prayer skills are linked to wider ethical ideas of human thriving in the Eastern Christian churches, where spiritual transformation through disciplined, embodied practice has long been considered a key purpose of religious engagement.