It is now commonplace in German Protestant churches to find private, non-liturgical candles burning in wordless prayer. These candles, lit by individuals who might spend little time in church themselves, represent a transformation of classical Protestantism that highlights shifts between public (congregational) and private (individual) religiosity, and perhaps between what we might call “institutional theology” and “individualistic spirituality.” If Martin Luther (1483-1546) were to visit a Protestant church in present-day Germany, he might be shocked to see the new forms of spirituality that have emerged there. Seeing the candles, Luther might be relieved to notice that the church had no statues, that the candles were lit before plain walls. However, he might be puzzled that the next Protestant church contains a huge statue of the Virgin Mary looking out onto a similar sea of candles and flyers filled with prayers and poetry. But, perhaps on further reflection, he might recognize in such practices some aspect of the Protestant Reformation that he began: namely, he recognize at the core of such practices an echo of the Reformation’s erasure of spiritual hierarchy and the dissolution of centralized power to grant or deny access to God.

***

In a time of social and religious unrest, the Protestant Reformation began in sixteenth-century Wittenberg (Germany) as the protest of a theologian and other academics against the practice of selling indulgences. Mainstream Protestantism of the Lutheran variety developed out of this protest. Lutheranism developed as a spirituality of reading and memorizing Bible verses, singing, listening to sermons, and reflecting on interior and exterior life. Theoretically, Protestants consider everyone equally close to God, and believe that people require neither human mediators for access to the divine nor a system for the distribution of holiness: salvation requires only faith. (That Protestant theologians thinking about the selection and pre-election of the faithful wrote very thick volumes and used their arguments as a means of power and guidance of the flock is no secret.) This flattening of the spiritual hierarchy made some religious practices obsolete: believing the sacrifice of Christ to have been made once and for all, Luther and other reformers saw no need for priests to re-enact that sacrifice in the mass, no cause to plead with saints to intercede on one’s behalf, and no justification for the practice of paying those seen as higher up in a spiritual hierarchy) to convey one’s prayers more effectively.

The lack of hierarchy was also reflected in the aesthetic of Protestant churches: the number of altars was reduced and statues of saints, no longer necessary as intercessors and guarantors of salvation, disappeared. Many churches changed from dimmed halls into bright prayer rooms, and the choir became largely useless, except for the occasional communion. The pulpit—always a symbol, its place and its decoration reflecting current understandings of the word of God and the role of the clergy—became the new liturgical center.

In the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, dialectical theology sought to purify the Protestant church of worldly contamination by erasing from it everything that did not correspond to the gospel. Again, pure faith was the only answer to God’s call. And again, the theology was expressed in the aesthetic of the church, especially the pulpit. The congregation was placed under the pulpit—under judgment—while the light of the gospel, or God’s grace, fell from above. But, in time, this authoritarian theology collapsed under its own weight. In the 1960s, people demanded new, more personal liturgies, as they sought greater self-expression in religion. Once again, the (re)placement of the pulpit was symbolic: in the 1960s and 1970s, they were lowered, or even removed, as pastors were no longer seen to stand above the congregations, handing down the word of God.

This re-flattening of the spiritual hierarchy was again accompanied by new possibilities of religious expression, including the lighting of individual candles in church. Though private candles had previously been associated with Catholic rituals, bringing light into the darkness of human existence as a symbolic act was close enough to biblical references, and it was not forbidden. Protestant churches developed installations for lighting candles. As with the pulpit, the form and placement of these installations can tell us something about the ongoing negotiation between private and public religiosity in Protestant churches.

***

Private, individual spirituality in public, Protestant space

As German Protestant churches function primarily as rooms for listening to public sermons, they do not need to be open except during services. There is nothing to be adored, no holy communication except at the time of the service. But, since some churches interest tourists, the congregations open their doors between services. Churches therefore serve a strange double purpose as spiritual hotspots and as non-functional symbols of the congregation’s hospitality and the institution’s openness. The current practice of individual candle lighting must be seen in this context. The churches are public, Protestant spaces; but the motivation to light a candle or to write down a prayer or a sentence is private, and is not bounded by faith or denomination.

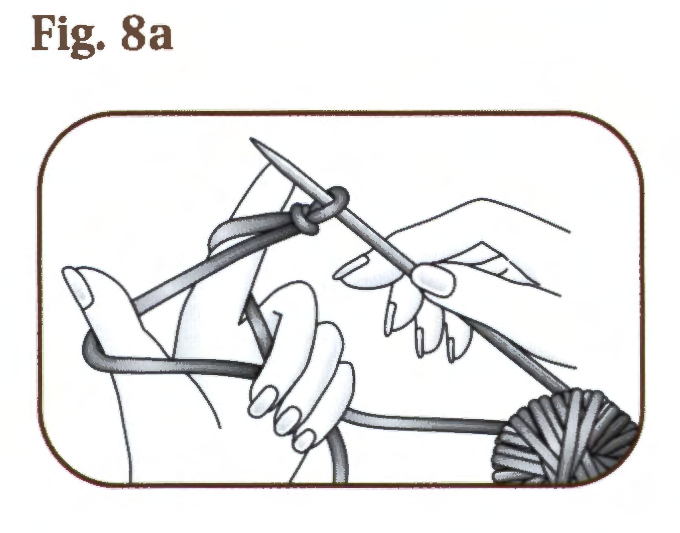

We can distinguish three main types of installations for lighting individual candles in Protestant churches. The first is close to the classic Catholic style.

We can distinguish three main types of installations for lighting individual candles in Protestant churches. The first is close to the classic Catholic style.

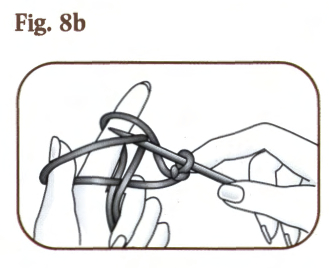

This installation—a sort of spiritual art—is on the floor of St. Peter’s church in Hamburg. It is in a state of constant change, as many visitors write and draw in the sand. There is a prayer on the wall behind the installation, but the theology of the prayer and the spiritual practice of the candles and sand are not the same. Perhaps the provided text is a way for the institution to make a Protestant statement, to serve as a guide in the act of turning candle lighting officially into a prayer, and to juxtapose the transience of writing in the sand with what one might consider the permanence of a plea to God. At the same time, the spiritually private nature of candle lighting and the individual nature of whatever one may write in the sand lets happen whatever may happen there. Quite often, one can see hearts and initials in the sand, presumably created by couples seeking heavenly protection for their love: this tradition speaks in a different spiritual register than the prayer on the wall.

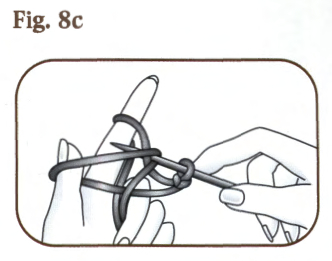

In St. Michael’s church in Hamburg, we see an example of the next style, the cauldron. Here, the candle installations illustrate the difficulty of adapting a liturgical space with its own history and architecture to changing patterns of spirituality. St. Michael’s is a baroque Protestant space resembling a theater, where everyone can see and hear the preacher on the huge pulpit. But, in this picture, we see a cauldron filled with sand in which to place decorated candles. This cauldron and another one just in front of the steps to the choir have been placed in places of no real significance. These are not spaces for prayer, solitude, or meditation—each is a sort of non-place, but within the spatial organization of a church building. Above the cauldron, a table shows numbers corresponding to songs to be sung during the service, but these things are in proximity, not in actual relation.

New forms of spirituality have no adequate place here—the church was not built to accommodate recent spiritual practices, but the need is obvious. This is spirituality seeking a place it has only found in the margins, not in the very center.

The Marktkirche in Hannover gives another example of candles and individual prayers in Protestant churches. In a number of churches, one may find a heavy bronze tree with candles placed at the end of the branches. The tree seems to blossom with fire, possibly in reference to the burning bush that Moses saw; to the grape, a biblical symbol of unity and individuality; or to the tree of life. (It seems to me that the variety of interpretations represents the postmodern openness of meaning.) In the Marktkirche, visitors may write down prayers to be read during the noon liturgy and pin them to the adjacent wall. The connection between the prayers and the tree of light is not obvious, though it may somehow be intended. The tree stands by itself as a strong symbol, and other practices seem to be minor. I interpret this lack of clarity as an unfinished search for adequate forms of emerging expressions of faith.

In the photograph, we also see a specifically Protestant spirituality in evidence. The locked trolley on the left contains the songbooks for the Sunday service: it serves only for public services, not for private prayers or candle lightning. There may be some uneasiness about the mixture of private and public piety.

***

The ability to light private candles in Protestant churches is one of many new expressions of faith. Installations like the ones examined here contrast the exclusively institutionally expression of faith with a more fluid and personalized spirituality, one that makes accommodations to personal needs and interests. That these Protestant spaces now offer the ability to light a candle is neither completely self-explanatory from the history of Protestant piety nor contradictory to it. It can be understood through the interaction of a fundamentally Protestant impulse and larger social trends towards personalization and individualized spiritual expression.