[Editor’s Note: This essay resides within Anderson Blanton’s “The Materiality of Prayer,” a portal into Reverberations’ unfolding compendium of resources related to the study of prayer.]

A key element in the practice of charismatic Christian healing prayer is the operation of a “spiritual gift” (charism) that allows the pray-er to discern the presence of illness-causing demons. Practitioners of faith healing often describe this “gift of discernment” specifically in terms of a divinely augmented sense of touch that allows the healer to detect the presence of unseen agents of illness within the body of the patient. Through this gift of the spirit, the sensory capacities of the mortal flesh are quickened with a preternatural capacity to sense the presence of that which, under everyday sensory regimes, persists undetected. Prominent faith healers such as William Branham, A. A. Allen, and Oral Roberts described this haptic quickening as a special sensation of “pressure,” “heat,” “electricity,” and “vibration” registered through the hand. The gift of discernment, therefore, is a divine prosthesis that allows the human hand to detect the spirit during the therapeutic performance of prayer.

A key element in the practice of charismatic Christian healing prayer is the operation of a “spiritual gift” (charism) that allows the pray-er to discern the presence of illness-causing demons. Practitioners of faith healing often describe this “gift of discernment” specifically in terms of a divinely augmented sense of touch that allows the healer to detect the presence of unseen agents of illness within the body of the patient. Through this gift of the spirit, the sensory capacities of the mortal flesh are quickened with a preternatural capacity to sense the presence of that which, under everyday sensory regimes, persists undetected. Prominent faith healers such as William Branham, A. A. Allen, and Oral Roberts described this haptic quickening as a special sensation of “pressure,” “heat,” “electricity,” and “vibration” registered through the hand. The gift of discernment, therefore, is a divine prosthesis that allows the human hand to detect the spirit during the therapeutic performance of prayer.

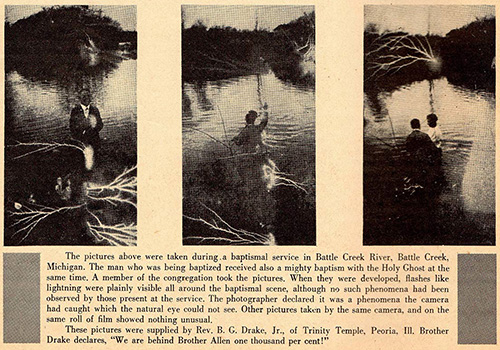

The divinely attuned capacities of the body, however, are not the only media for the detection of the spirit. Artificial devices and material objects have also played a crucial role in the discernment of sacred presence, and reveal striking homologies with the specifically somatic gift previously described. Take for example the sensitive capacities of the camera’s mechanical eye, simultaneously revealing sacred structures and organizing particular experiences of “belief” for the viewer. More specifically, mass circulated Pentecostal magazines included photographs that were described as having registered sacred presences unavailable to the naked eye (see illustration from A. A. Allen’s Miracle Magazine). As an influential precursor to Pentecostalism, the “spirit photography” of nineteenth century American Spiritualism also relied heavily upon the camera and the photographic plate to reveal spectral forces circulating beyond the capacities of everyday sensation.

One of the most popular holy cards of the twentieth century showed the southern Italian stigmatic Padre (now Santo) Pio, saying mass, his bloody hands folded in prayer, and included a tiny piece of stained fabric that had been touched to his wounds. But all holy cards were media of presence. The devout kissed them; they held them while they prayed; the cards were exchanged from hand to hand; they were tucked into the frames of bedroom mirrors and taped to walls. They were used in the making of household shrines. Holy cards were carried into all the spaces of the modern world, onto battlefields in soldiers’ pockets, for example, into industrial and post-industrial workplaces, and especially into hospitals.

One of the most popular holy cards of the twentieth century showed the southern Italian stigmatic Padre (now Santo) Pio, saying mass, his bloody hands folded in prayer, and included a tiny piece of stained fabric that had been touched to his wounds. But all holy cards were media of presence. The devout kissed them; they held them while they prayed; the cards were exchanged from hand to hand; they were tucked into the frames of bedroom mirrors and taped to walls. They were used in the making of household shrines. Holy cards were carried into all the spaces of the modern world, onto battlefields in soldiers’ pockets, for example, into industrial and post-industrial workplaces, and especially into hospitals.