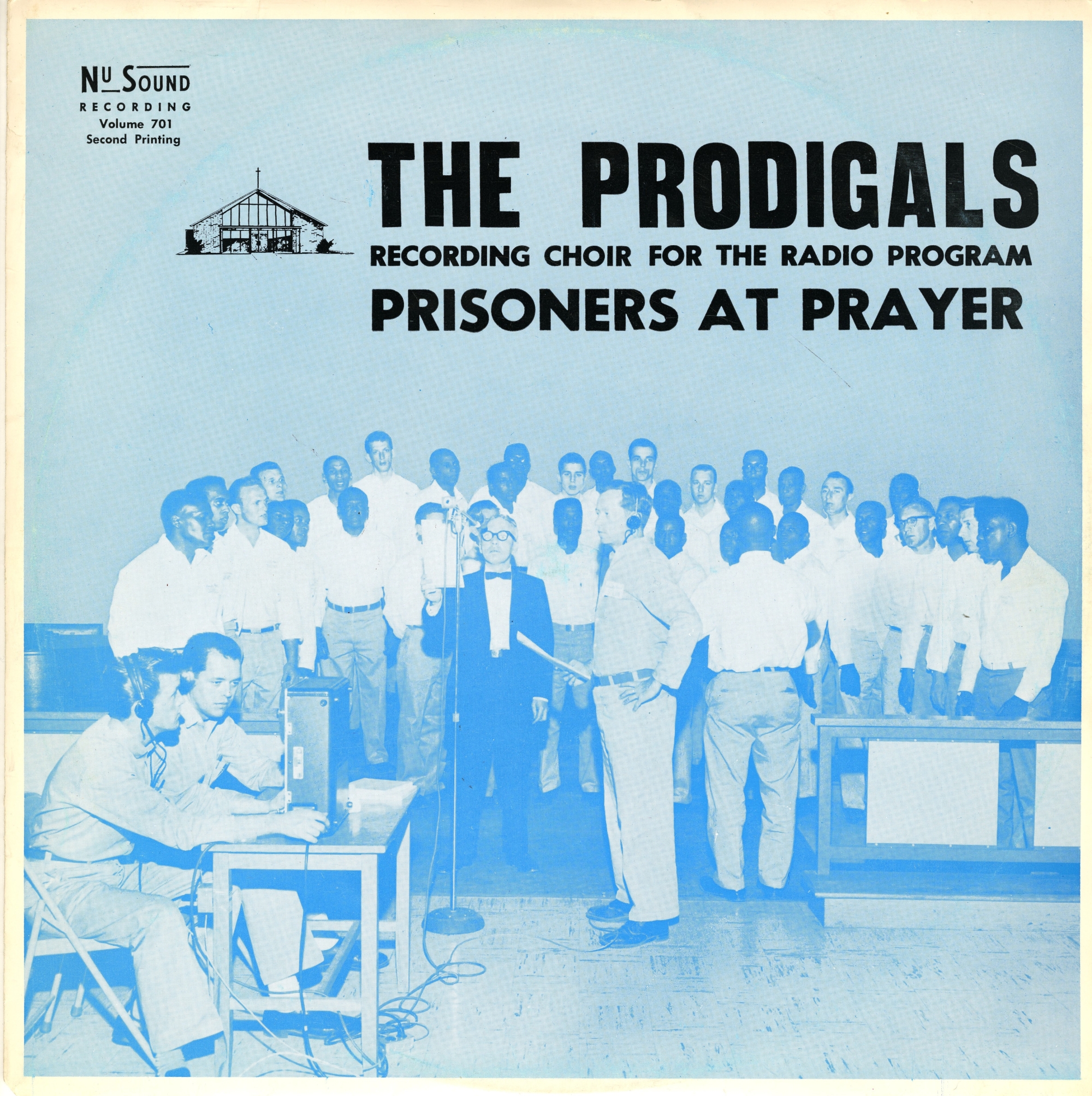

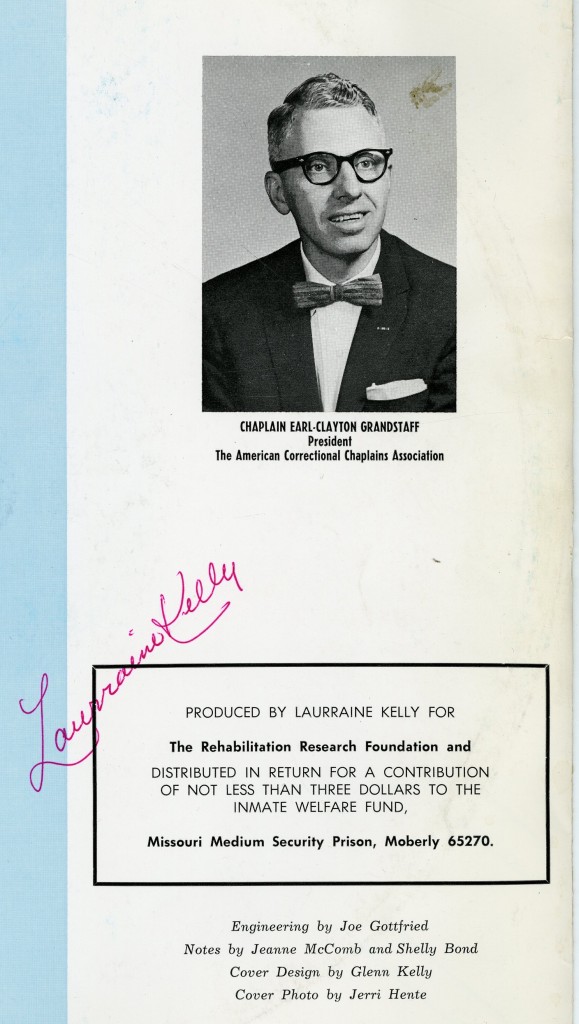

Prisoners at Prayer (Nu-Sound Records) was arranged and produced under the auspices of Chaplain Earl-Clayton Grandstaff. Grandstaff was an ordained Baptist minister and the author of A Study of Correctional Chaplaincy Service (1966). His was a mixture of benevolent reform, faith in redemption, and spectacle. The novelty of reformed criminals is quite palpable on this album. As deviant peculiarity gives way to choral coordination in your ears and in front of your eyes, you cannot help but think of the Foucauldian framing, perhaps only through it.

“Prisoners are people . . . yet visitors never cease to marvel at the personality and performance of prisoners,” says Superintendent Ed Haynes of the Missouri Medium Security Prison in Moberly, Missouri. Liberal conscience is emboldened here, swayed by the righteousness of its cause, its knowledge of being in the right. As reported in the liner notes, Haynes “welcomes students and serious visitors to what has been called a ‘bold venture of faith about the inherent goodness within every man . . . Truly NO MAN IS AN ISLAND when prisoners are at prayer.”

“Prisoners are people . . . yet visitors never cease to marvel at the personality and performance of prisoners,” says Superintendent Ed Haynes of the Missouri Medium Security Prison in Moberly, Missouri. Liberal conscience is emboldened here, swayed by the righteousness of its cause, its knowledge of being in the right. As reported in the liner notes, Haynes “welcomes students and serious visitors to what has been called a ‘bold venture of faith about the inherent goodness within every man . . . Truly NO MAN IS AN ISLAND when prisoners are at prayer.”

As the unattributed blurb on the sleeve attests, we have here “a really unique choir, performing a public service for the listener and for the participant alike, whether incarcerated or a member of the ‘free society’ …” The scare quotes seem to offer a rebuke of sorts, a reminder, a stinging criticism of the way in which members of the free society casually hold their assumptions.

This is the Way I Pray / in my home / in my home/ hallelujah

Foucault theorized secularization, that is, the difference of modernity and the difference that that difference makes as one goes on and about living. He defined secularization, implicitly, as the diffusion of ecclesiastical forms into every crevice of social life. Here was an unprecedented intensification of what Foucault called biopolitics. The power of the pastorate had become a shadow of its former self. Yet it had washed over the population at the level of the population, there being no analytic outside to the population these days of Google Glass™. Pastoral power was now decoupled from any particular individual, dematerialized for the most part, and transformed into a formal proposition of the state apparatus. Foucault’s notion of secularization was also a fascinating story about the birth of the modern subject. It is counterintuitive. It is tension-filled. It wants to close in upon itself. For according to Foucault, the state’s overwhelming power stemmed from its capacity to individualize and totalize simultaneously.

In “This is the Way I Pray,” there is a fine line between intentionality and declarations about one’s intentionality. To think about this fine line leads one to ponder the practices of belief and to consider the content of belief in relation to practice. It leads one to consider how those practices intersect other practices. The focus being on ‘this is how I pray’ as much as, if not more than, what I pray to or for or about.

This is the Way I Pray / in my home / in my home/ hallelujah

Tags: belief, biopolitics, Michel Foucault, reform, secularization