[Editor’s Note: This essay resides within Anderson Blanton’s “The Materiality of Prayer,” a portal into Reverberations’ unfolding compendium of resources related to the study of prayer.]

Citing literary references from the fourteenth century, a folklorist lecturing on the history of the Rosary provocatively stated, “the word ‘bead’ (Anglo-Saxon beade or bede) meant originally ‘a prayer.’” Despite such early etymological gestures toward an inextricable relation between prayer and the material object, however, formative debates within anthropology and religious studies can be seen as precisely an attempt to isolate the practice of prayer from its material conduits. More specifically, participants in these formative debates have often described the history of prayer (and concomitantly the evolution of religion) as a progressive movement of abstraction from the mechanical efficacy of the thing itself (incantation, object, and gesture) toward an increasingly intellectual endeavor beholden to the contingent demands of “faith.” Such narrations of prayer as a developmental history of interiorization into the cognitive recesses of the modern subject have had lasting consequences for the academic study of religion.

Scholars have tended to describe prayer as a predominantly intellectual act oriented by the exercise of volition, generally neglecting the way these imagined inner experiences are intimately related to bodily techniques, material objects, technologies and built environments which subsist and circulate “outside” the cognitive interiorities of the religious subject. In short, the academic theorization of prayer itself mimics a crucial performative moment in the history of Protestant faith healing: at the very moment when the patient must make tactile contact with a material supplement to open a communicative relay between the sacred and the everyday, the proscriptions of the curative technique simultaneously renounce the objectile through the phrase, “Only Believe!” (see for instance: The Radio as Prosthesis of Prayer).

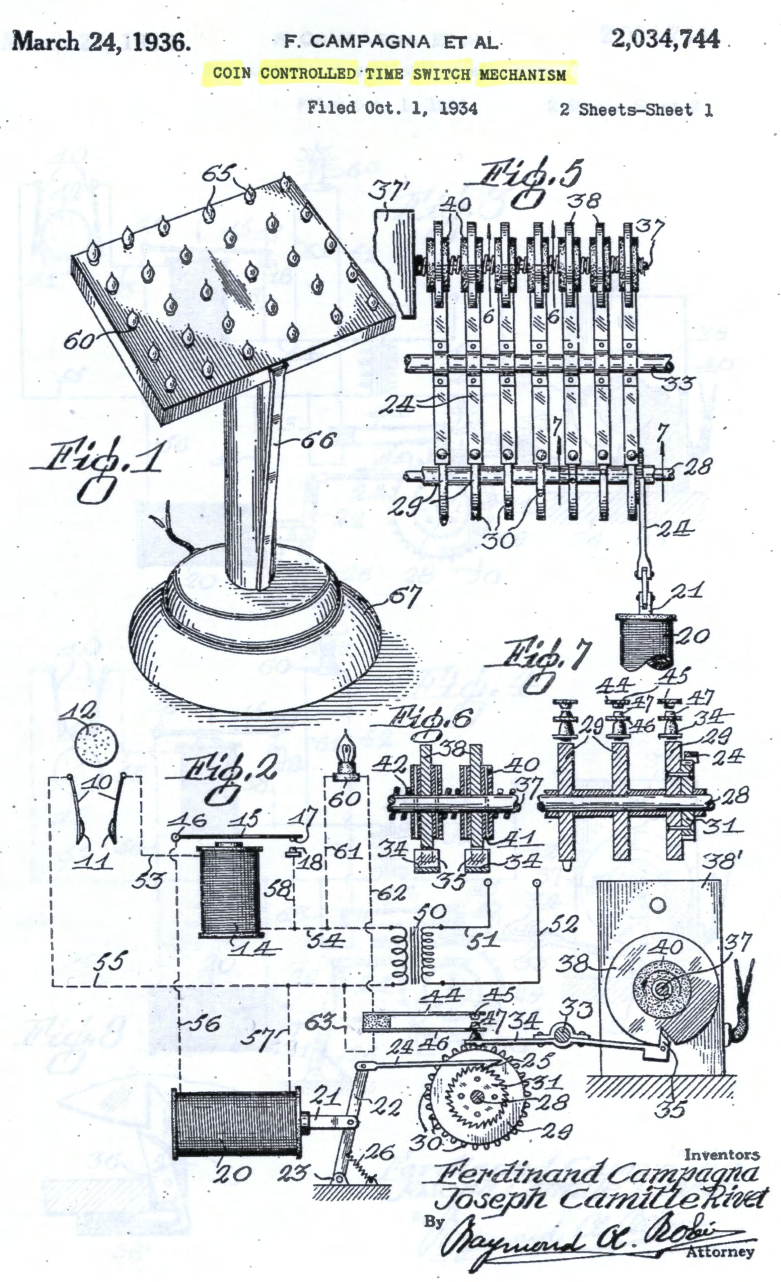

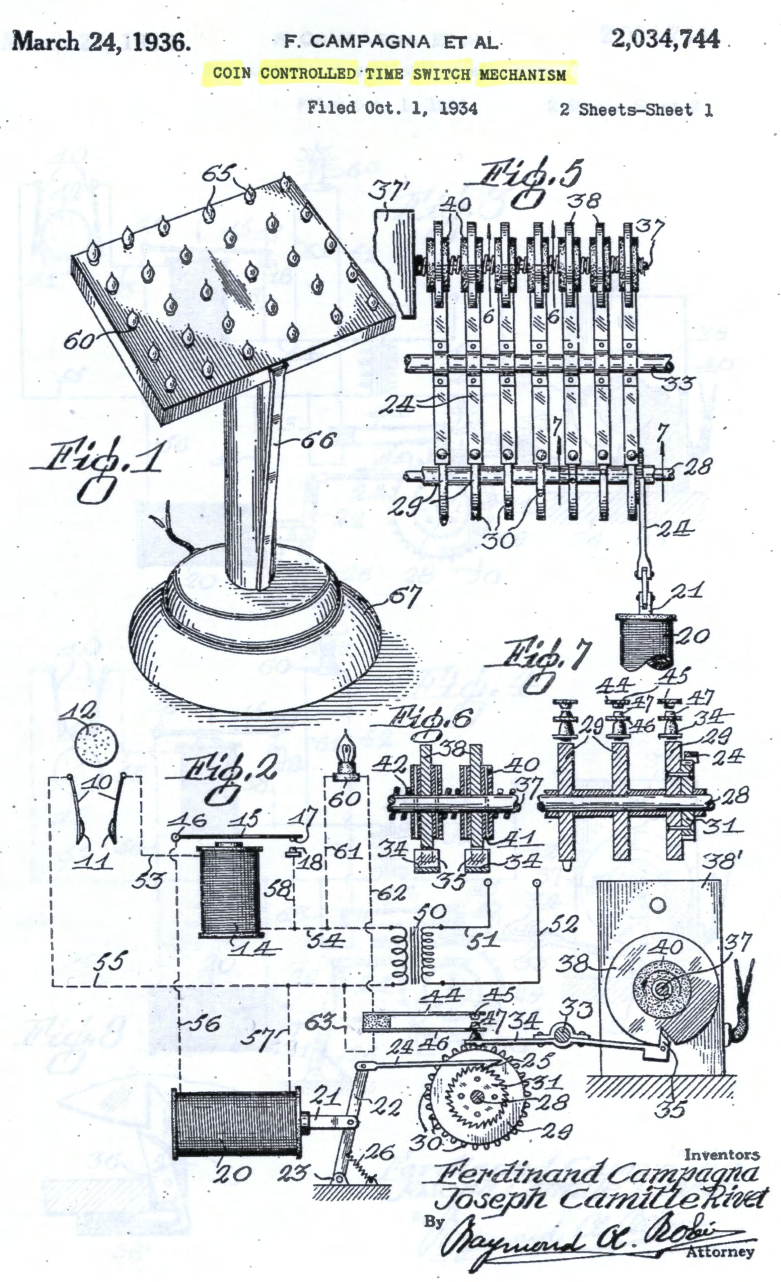

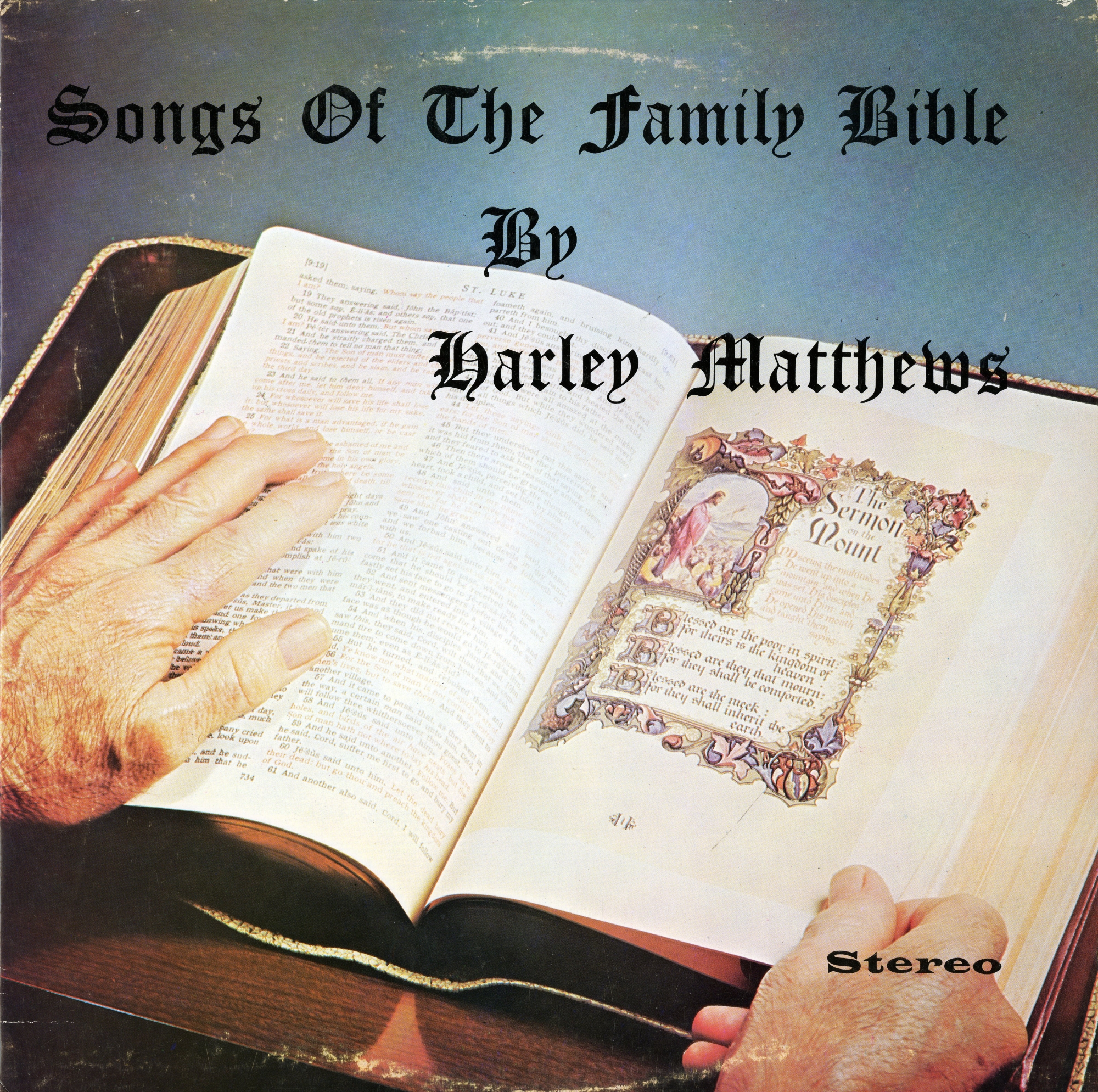

Against this foundational narrative of prayer as a history of abstraction, this collection of objects seeks to recuperate the old etymological resonances of prayer as a “bead,” as a gloss for both materiality and mechanized rhythms or repetitions (see for instance: Electric Votive). In so doing, this exhibition explores the ways in which prayer is intimately intertwined with material objects that actively organize performative techniques and embodied experiences within the practice of prayer. A new definition of prayer emerges from this focus on materiality. Unencumbered by a long history of scholarship that conceives of prayer strictly in terms of articulations of the voice and an interior circuitry of will and representation, the materiality of prayer collection describes prayer as a particular sensory attunement emerging at the interface between the assumed everyday capacities of the body and its technological extensions and material supplementations. Articulating the shifting sensorial registers organized in different religious traditions and technological environments, this collection will demonstrate that the social and experiential force of prayer often subsists within sensations that reverberate before or beneath the clearly demarcated intellectual categories of “belief.” This collection will concretely describe a new history of prayer, not as a retreat into the silent recesses of the religious subject, but as a progressive exteriorization through media technologies and material objects into the “apparatus of belief.”

In response to Winni Sullivan’s astute analysis of Town of Greece v. Galloway, I want to probe her claim that “prayers are tamed by law,” before looking in a little more detail at the content of these public prayers. On one level, the claim is straightforward enough. Scholars of law and religion use “law’s words and law’s aesthetics” to “describe and judge” the prayers. Public prayers come under the jurisdiction of legal terminology in an analysis that is highly textual. But the more fascinating and challenging claim is that, prior to this academic surveillance operation, the pray-ers/prayers themselves have already spontaneously become law. This sounds like a contemporary Foucauldian story about the internalisation of law’s discipline. But there are also echoes of an older story, told by (for example) Aristotle, Seneca, and Paul. Law is not the real thing, the thing in itself, but an eikon (image) of the good society. The good person, the god-like person, becomes living law.

In response to Winni Sullivan’s astute analysis of Town of Greece v. Galloway, I want to probe her claim that “prayers are tamed by law,” before looking in a little more detail at the content of these public prayers. On one level, the claim is straightforward enough. Scholars of law and religion use “law’s words and law’s aesthetics” to “describe and judge” the prayers. Public prayers come under the jurisdiction of legal terminology in an analysis that is highly textual. But the more fascinating and challenging claim is that, prior to this academic surveillance operation, the pray-ers/prayers themselves have already spontaneously become law. This sounds like a contemporary Foucauldian story about the internalisation of law’s discipline. But there are also echoes of an older story, told by (for example) Aristotle, Seneca, and Paul. Law is not the real thing, the thing in itself, but an eikon (image) of the good society. The good person, the god-like person, becomes living law.

Underneath the massive cloth architecture of Oral Roberts’ canvas cathedral, the “world’s first healing film” was screened for a crusade audience of over 10,000 on September 29th, 1952. Venture Into Faith is a compilation of actual archival footage shot earlier that year during a healing crusade in Birmingham, Alabama, woven seamlessly into highly produced scenes recorded in a Hollywood studio. The climax of the film, for example, features the miraculous cure of a tubercular boy named David through a performance of prayer. Although the actual performance of this healing prayer was performed by Oral Roberts and a group of professional actors, the final edited version of this spectacle of divine communication oscillates between “live” archival footage shot during a healing campaign and rehearsed “acting” recorded under the careful orchestration of a Hollywood director (1:23:39 in film).

Underneath the massive cloth architecture of Oral Roberts’ canvas cathedral, the “world’s first healing film” was screened for a crusade audience of over 10,000 on September 29th, 1952. Venture Into Faith is a compilation of actual archival footage shot earlier that year during a healing crusade in Birmingham, Alabama, woven seamlessly into highly produced scenes recorded in a Hollywood studio. The climax of the film, for example, features the miraculous cure of a tubercular boy named David through a performance of prayer. Although the actual performance of this healing prayer was performed by Oral Roberts and a group of professional actors, the final edited version of this spectacle of divine communication oscillates between “live” archival footage shot during a healing campaign and rehearsed “acting” recorded under the careful orchestration of a Hollywood director (1:23:39 in film).