Bread of Life: The Word/The Silence

Directed by Klára Trencsényi and Vlad Naumescu. India/Hungary, 2014

The Bread of Life series consists of two short documentaries about modes of Christian devotion and spiritual pursuit in South India today. Shot between October 2013 and February 2014 as part of Vlad Naumescu’s research on Syrian Christians (St. Thomas Christians) in India, the films explore Orthodox Sunday schools and Christian ashrams, taking a different cinematic approach in each case to grasp their distinct rhythms of prayer. Together, the two films contrast a pedagogy of prayer centered on speech and recitation with one based on silence and contemplation. Each draws on a model of ethical formation that ties together certain values, practices, and aesthetics to shape a Christian personhood.

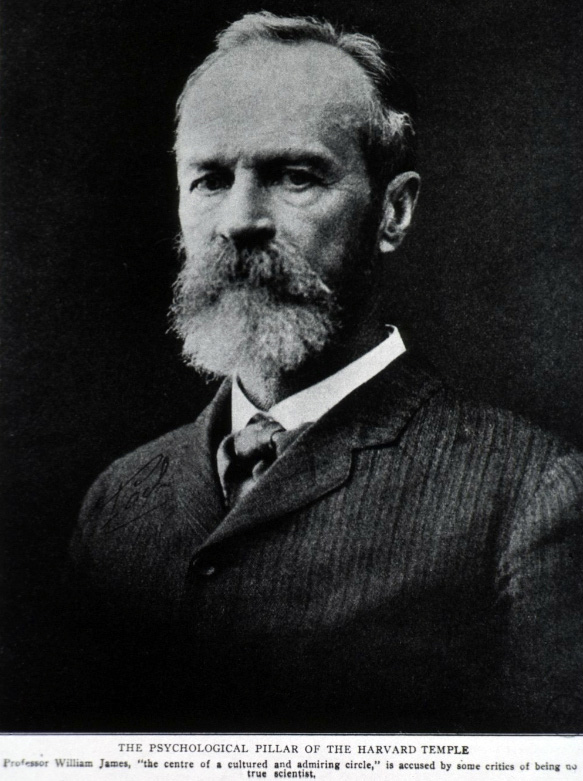

Pedagogies of prayer reflect not only what and how one should learn to address God but also what one can know and what remains unknown. They reveal the strong connection between aesthetic formations (as explored in this portal) and folk epistemologies or theories of mind—models people employ to reason about their and others’ intentions, behavior, and knowledge (see Tanya Luhrmann; Rita Astuti). Such models inform the religious pedagogies and practices Naumescu observed among Syrian Christians in India and, ultimately, their experiences of God.

The Syrian Christian churches in Kerala trace their origins to the first century AD when St. Thomas the Apostle converted a few Hindu families—hence their name, “St. Thomas Christians.” Their history, marked by shifting colonial regimes, intense missionary activity, and intricate relations with Catholic, Middle Eastern, and Protestant churches, records several schisms among them. Today, this community (about three million just in Kerala) has a distinct identity and high caste status within Keralite society. It is split into eight churches, each claiming to be the true inheritor of the St. Thomas tradition: two of these churches are Catholic, one Anglican, one Nestorian, three Antiochian and one Episcopalian. This history affects their rites and liturgies, the devotional culture, and institutional formation; despite this diversity, Syrian Christians remain rooted in the same indigenous tradition and share a spiritual heritage that crosses institutional boundaries and present-day competition. (Joseph, M.P., Uday Balakrishnan, and István Perczel. “Syrian Christian Churches in India.” In Eastern Christianity and Politics in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Lucian N. Leustean, 563-599. Routledge, 2014)

The first film, The Word looks at Sunday school education among Jacobite Syrian Christians through the eyes of Aleesha, a thirteen-year-old girl from St. Mary cathedral in Ernakulam. A very talented and ambitious pupil, Aleesha takes part in many competitions on behalf of her Sunday school, one of the most successful in the Jacobite Orthodox church. In the film, she participates with a speech on Jesus as the Bread of Life, the theme of the annual competition in 2014. Aleesha spent six months rehearsing the speech in preparation for this event. Her speech, entirely written by the Sunday school headmaster, plays on the double-meaning of Appam, the daily “bread” in South India, but also the bread that becomes Jesus’ body in the Eucharistic liturgy (Holy Qurbana). Aleesha says this is a “mystery,” following the Orthodox conception of sacraments as mysteries that cannot be fully grasped or put into words.

In Eastern Christianity, mysteries are usually experienced in liturgical practice; churches put more emphasis on learning through liturgical participation rather than on formal instruction. Sunday schools appeared in the Malankara church through the efforts of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) to establish religious education, introduce vernacular language, and purify the rite of various influences. The shift from practical to didactic reshaped people’s relationship to ritual and made speech, whose persuasive power resonates well with Keralite oratory, central to one’s faith and worship. In doing so, it also placed more pressure on the youth, as the hopes of this Syrian Christian community turned towards them as potential bearers of faith and of their social aspirations.

The second film, The Silence, guides us through the everyday life of a contemplative Christian ashram belonging to the same family of Syrian Christian churches (the Syro-Malankara Church). For the Indian monks in this ashram silence is a mode of expectation and preparation for an encounter with Jesus, whether in the form of Eucharistic bread or in the guise of a stranger. Silence or stillness (hesychia) is perhaps the ultimate expression of Orthodox apophaticism, the negative theology emphasizing that God is beyond human understanding and speech. Monks try to dwell in this stillness while pursuing their daily chores and welcoming visitors. The film camera breaks the silence for a moment as the monks agree to send a video letter to the family of the founder, Francis Mahieu (Acharya) on the occasion of their family reunion in Belgium. The moment is opportune: the monks are about to elect their new abbot and the film offers them the opportunity to reflect on their lives, on Acharya’s heritage, and on the challenge of finding someone to follow in his steps. Francis, a Belgian Cistercian monk, arrived in India in the wake of its independence and built a community in Kurisumala that pioneered Christian inculturation and Gandhian economics. It’s been more than ten years since he died, but his vision lives on, not least through their bread-labor. Their “daily bread” is a concrete materialization of this intimate relationship that crosses time and space: the dark bread they knead reminds them of Acharya’s journey, while the Eucharistic bread embodies the hope for the spiritual transformation he envisioned.