[Editor’s Note: This essay resides within Anderson Blanton’s “The Materiality of Prayer,” a portal into Reverberations’ unfolding compendium of resources related to the study of prayer.]

* * *

Part I in an ocasional series by Don Seeman on the materiality of Jewish prayer.

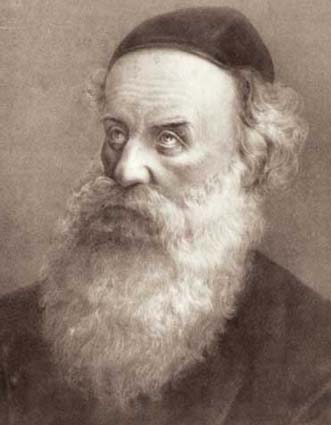

Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812), the so-called Alter Rebbe, or founding teacher of the Chabad movement, was once asked to explain to his students how he prays. He is said to have responded, “I pray with the table and with the chairs.” When I first heard this story many years ago, I assumed he meant merely to say that he prayed with great intensity, so that the tables and chairs shook with his fervor. Anyone who has seen Orthodox Jews engrossed in speaking to their Creator while bowing and shaking in constant motion—shuckling, as it is sometimes known in English— will know what I had in mind. I was more wrong than right though, because I underestimated the central importance of tables and chairs and the whole world of mundane materiality to Hasidic prayer. Far from being merely a backdrop or a disturbance to the pursuit of pure spirituality, it is precisely the material world that serves as the setting and telos of Hasidic prayer, whose ultimate agenda is to render—or better, to reveal—this mundane space we inhabit as a fitting habitation for divinity, or what they call dirah ba-tachtonim, “a home in the nether regions.” But what does all this have to do with tables and chairs?

Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812), the so-called Alter Rebbe, or founding teacher of the Chabad movement, was once asked to explain to his students how he prays. He is said to have responded, “I pray with the table and with the chairs.” When I first heard this story many years ago, I assumed he meant merely to say that he prayed with great intensity, so that the tables and chairs shook with his fervor. Anyone who has seen Orthodox Jews engrossed in speaking to their Creator while bowing and shaking in constant motion—shuckling, as it is sometimes known in English— will know what I had in mind. I was more wrong than right though, because I underestimated the central importance of tables and chairs and the whole world of mundane materiality to Hasidic prayer. Far from being merely a backdrop or a disturbance to the pursuit of pure spirituality, it is precisely the material world that serves as the setting and telos of Hasidic prayer, whose ultimate agenda is to render—or better, to reveal—this mundane space we inhabit as a fitting habitation for divinity, or what they call dirah ba-tachtonim, “a home in the nether regions.” But what does all this have to do with tables and chairs?

The Chabad movement began to take hold in the Jewish communities of White Russia and Lithuania more than two hundred years ago and has developed today into an important global network of “emissaries” and spiritual entrepreneurs devoted to the promotion of Hasidic ideals and practice in every conceivable format and context. In its origins though, the movement was premised on intensive forms of contemplative study and prayer designed to transform human beings by focusing not on the emotions like other Hasidic groups, but on the intellect. The term Chabad itself is a Hebrew acronym for “wisdom, understanding, knowledge,” which represent the cognitive faculties targeted by these practices. Interesting comparisons with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy have recently been advanced. Active contemplation of paradoxes like the coincidence of divine immanence and transcendence helped to fill the mind of the worshipper with divine light, which alone could offer lasting transformation of human affect and ultimately, it was to be hoped, of human practice and existential condition as well. (more…)