My mother used to tell the following story: My father was a rabbi in Houston, Texas, where I was born. In those days, rabbis and cantors wore long black gowns and squared hats on the pulpit, and the synagogue had an organ and a choir. One evening, as the cantor recited Kiddush (the prayer over wine announcing the beginning of the Shabbat), I looked at the cantor and asked, “Mama, is that God?” The story became apocryphal in the family but, unlike other children, I did not give up pondering the question, “Who is God.” It stayed with me as we left Texas and moved to New York. It remained a part of me as I went through several schools, culminating in a Jewish day school where we had a double curriculum, the Judaic part of which was taught in Hebrew. There, I added a new dimension to my pondering: texts. The words of Isaiah, Jeremiah, the Torah, the Siddur (prayer book), and much more fit naturally in my memory, much as math or art or social skills fit naturally into the memory of others. God was, in some way, always at the center.

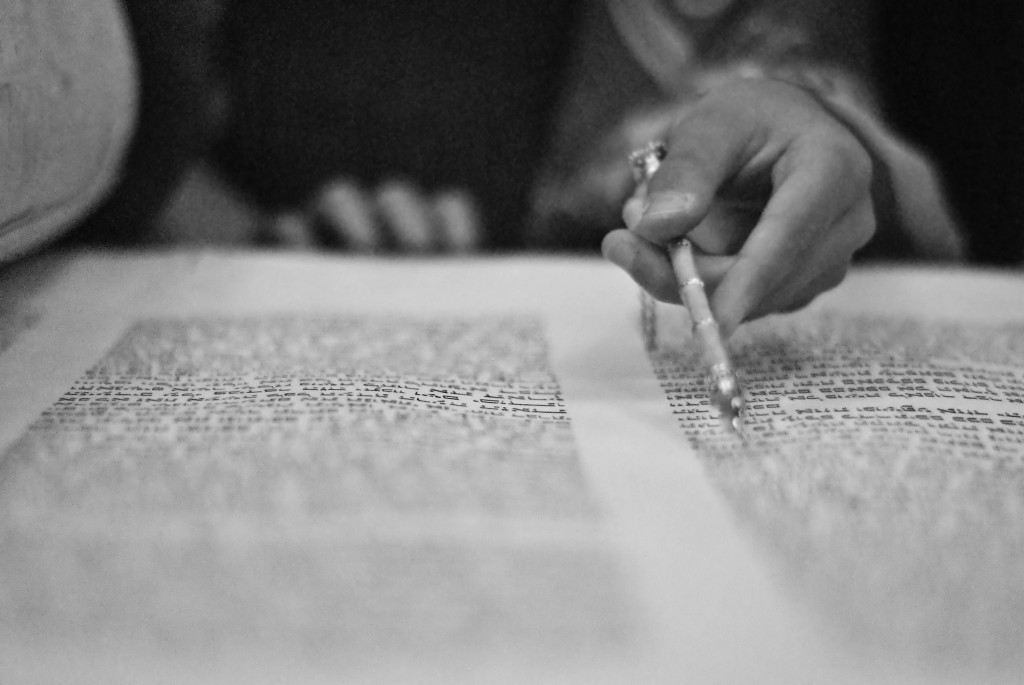

My mother used to tell the following story: My father was a rabbi in Houston, Texas, where I was born. In those days, rabbis and cantors wore long black gowns and squared hats on the pulpit, and the synagogue had an organ and a choir. One evening, as the cantor recited Kiddush (the prayer over wine announcing the beginning of the Shabbat), I looked at the cantor and asked, “Mama, is that God?” The story became apocryphal in the family but, unlike other children, I did not give up pondering the question, “Who is God.” It stayed with me as we left Texas and moved to New York. It remained a part of me as I went through several schools, culminating in a Jewish day school where we had a double curriculum, the Judaic part of which was taught in Hebrew. There, I added a new dimension to my pondering: texts. The words of Isaiah, Jeremiah, the Torah, the Siddur (prayer book), and much more fit naturally in my memory, much as math or art or social skills fit naturally into the memory of others. God was, in some way, always at the center.

David R. Blumenthal

David R. Blumenthal is the Jay and Leslie Cohen Professor of Judaic Studies at Emory University, and is a member of the European Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Religion. Professor Blumenthal did path-breaking work in medieval intellectual Jewish history with his early studies in Yemenite philosophy, his two-volume textbook on Jewish mysticism (Understanding Jewish Mysticism), and his later work that established the concept “philosophic mysticism” as a category of analysis in medieval philosophy and mysticism. Professor Blumenthal also did very innovative work in modern Jewish religious thinking: in spiritual theology (God at the Center), in post-shoah theology (Facing the Abusing God: A Theology of Protest), and in social psychology and moral education in the post-shoah era (The Banality of Good and Evil: Moral Lessons from the Shoah and Jewish Tradition). In addition, Professor Blumenthal was among the earliest scholars to use multi-textual writing (“Reading Genesis,” “Praying Ashrei,” “The Creator and the Computer,” and "Text-ing" in Facing the Abusing God: A Theology of Protest). He has also encouraged students to write creative essays and has put up their work on his website. Finally, Professor Blumenthal has reached out from Religious and Jewish Studies to the arts and, together with his wife Ursula, has curated an exhibit of Salvador Dali’s suite of lithographs, “Aliyah, the Rebirth of Israel.” He has taught a course on the Akeda and its expression in art, sculpture, literature, and music. And he has hosted a course on Israeli and Topical Judaica Philately based upon the holdings of Emory University.

Posts by David R. Blumenthal

November 17, 2015

Insights

A portal, or a book, can be read in many ways. Some people read from the beginning to the end; others use tables of contents and indexes to search out material; still others jump around at will. That is true of this portal too: One can follow the table of contents that, itself, follows the order of the Siddur. Or, one can use the search function to seek materials that sound interesting or appealing. Or, one can browse through these Insights about Jewish prayer. Any method works.

To facilitate movement among the Insights presented and also between the various sections of the portal, I have embedded links to material that appears elsewhere. Only sustained study, however, can give one a sense of the interwoven character of the material. One must follow the links, reflect, and then go back to the various interlinked texts.

For further reference, I have embedded links to the WorldCat. This site, which has cataloged over two billion books, gives the reader a full bibliographical reference, and if one sets the WorldCat page properly, it will also identify the closest library with a copy of the book.

Finally, for those who read Hebrew, I have included a transliteration of the original texts. It is meant to be readable and does not pretend to be scientifically correct.

November 17, 2015

Thoughts

A portal, or a book, can be read in many ways. Some people read from the beginning to the end; others use tables of contents and indexes to search out material; still others jump around at will. That is true of this portal too: One can follow the table of contents that, itself, follows the order of the Siddur. Or, one can use the search function to seek materials that sound interesting or appealing. Or, one can browse through these Thoughts about Jewish prayer. Any method works.

To facilitate movement among the Thoughts presented and also between the various sections of the portal, I have embedded links to material that appears elsewhere. Only sustained study, however, can give one a sense of the interwoven character of the material. One must follow the links, reflect, and then go back to the various interlinked texts.

For further reference, I have embedded links to the WorldCat. This site, which has cataloged over two billion books, gives the reader a full bibliographical reference, and if one sets the WorldCat page properly, it will also identify the closest library with a copy of the book.

Finally, for those who read Hebrew, I have included a transliteration of the original texts. It is meant to be readable and does not pretend to be scientifically correct.

November 17, 2015

Meditations

A portal, or a book, can be read in many ways. Some people read from the beginning to the end; others use tables of contents and indexes to search out material; still others jump around at will. That is true of this portal too: One can follow the table of contents that, itself, follows the order of the Siddur. Or, one can use the search function to seek materials that sound interesting or appealing. Or, one can browse through these Meditations about Jewish prayer. Any method works.

To facilitate movement among the Meditations presented and also between the various sections of the portal, I have embedded links to material that appears elsewhere. Only sustained study, however, can give one a sense of the interwoven character of the material. One must follow the links, reflect, and then go back to the various interlinked texts.

For further reference, I have embedded links to the WorldCat. This site, which has cataloged over two billion books, gives the reader a full bibliographical reference, and if one sets the WorldCat page properly, it will also identify the closest library with a copy of the book.

Finally, for those who read Hebrew, I have included a transliteration of the original texts. It is meant to be readable and does not pretend to be scientifically correct.

November 17, 2015

Mystical Meditations

A portal, or a book, can be read in many ways. Some people read from the beginning to the end; others use tables of contents and indexes to search out material; still others jump around at will. That is true of this portal too: One can follow the table of contents that, itself, follows the order of the Siddur. Or, one can use the search function to seek materials that sound interesting or appealing. Or, one can browse through these Mystical Meditations about Jewish prayer. Any method works.

To facilitate movement among the Mystical Meditations presented and also between the various sections of the portal, I have embedded links to material that appears elsewhere. Only sustained study, however, can give one a sense of the interwoven character of the material. One must follow the links, reflect, and then go back to the various interlinked texts.

For further reference, I have embedded links to the WorldCat. This site, which has cataloged over two billion books, gives the reader a full bibliographical reference, and if one sets the WorldCat page properly, it will also identify the closest library with a copy of the book.

Finally, for those who read Hebrew, I have included a transliteration of the original texts. It is meant to be readable and does not pretend to be scientifically correct.

October 24, 2013

Praying Angry—A Jewish View

[Editor’s Note: This post is in response to “Praying Angry” by Robert Orsi.]

Bob Orsi’s “Praying Angry” shows a sensitivity to the victims of clerical abuse within the Catholic Church that is much needed. Based on interviews with a circle of survivors, and particularly with a former priest, Frank, Orsi sets forth some of the difficulties such survivors have with prayer and he presents Frank’s advice to survivors.

Bob Orsi’s “Praying Angry” shows a sensitivity to the victims of clerical abuse within the Catholic Church that is much needed. Based on interviews with a circle of survivors, and particularly with a former priest, Frank, Orsi sets forth some of the difficulties such survivors have with prayer and he presents Frank’s advice to survivors.

The core of the problem for Catholic survivors of clerical abuse is the teaching that the Catholic priest is an alter Christus, someone who is elevated, as Orsi puts it, “to higher ontological levels than other humans.” This makes clerical abuse not only a human betrayal, but betrayal in the spiritual life of the believer, even if the believer continues to believe and to participate in Catholic liturgy. Jews have a completely different relationship to their clergy: Rabbis are hired, and fired, by the congregation. No one would dream of thinking of his or her rabbi as alter Deus. Rabbis are people, and they are as subject to sin as anyone else. If they sin, they need to repent, and that usually includes punishment. Clergy abuse is wrong; guilty clergy should be handled by psychotherapy and/or prosecution. Any attempt to cover up clergy abuse is wrong, and should be handled by civil suit. This is largely what actually happens in the various Jewish communities, although resistance runs higher in some than in others. It is true that spiritual leaders, beginning with Moses, face higher expectations; but they are not alter Deus.

It seems to me, as an outsider with some experience in Jewish-Catholic dialogue, that the Catholic Church would be on much safer spiritual and theological grounds if it regarded its clergy as extraordinary human beings who are willing to make sacrifices that almost all of us reject in order to preach and practice the doctrines of the Church. And, indeed, the overwhelming number of religious are exactly that; like the rest of us, only an extremely small percent of clergy fall. As a corollary, the Church should never cover up cases of clerical abuse. The investigative procedure needs to be thorough, but completely honest. Those who do fall, after all, are sinners no matter how high they fall from.

The problem of how to pray after abuse (clerical or other; for Jews, this includes national abuse as in the shoah) is a different problem. It is serious both emotionally and theologically. How does one “pray angry,” as Frank puts it?

Frank nicely articulates the Catholic theological framework of his question by pointing out that life and prayer take place in the context of “suffering, death, and resurrection”; that we would all like to live in resurrection mode, but life is not like that. Jews do not share this theology. For Jews, suffering is not redemptive. It is bad for everyone, even for God, when there is suffering. Death, too, is not redemptive in a salvational sense, though it may be a blessing and relief for certain people who are suffering. Rather, death deprives us of the opportunity to serve God through His commandments which are all rooted in materiality. Resurrection gives us a second chance to serve God. In and of itself, resurrection is not salvational either.

For Jews, the issue in prayer after abuse is justice. We are commanded to resist evil (“You who love the Lord, hate evil” Ps. 97:10). If there is evil in the world, we must fight it as best we can. One can even argue that, if God has ‘done evil,’ it is our obligation to protest. Evil creates a tradition of socio-political, and theological, protest.

For this reason, I agree with Frank’s response, “Being honest with God entails holding God accountable.” As Orsi puts it:

Survivors have got God’s number; they meet God without illusions about God. But this does not drive them away from God, or it need not do so in Frank’s theology. Rather, it permits them to pray fearlessly and freely, to pray as they really are as persons, to open their inner lives in all their turmoil and anger to God who must take them as they are… Refusal of closure restores tension.

In the context of religious life after the shoah, I wrote a terrifying book called Facing the Abusing God: A Theology of Protest. I began with a theological prolegomenon on how to think about God. I, then, moved to textual study and, then, to dialogue with a survivor and a theologian. Then came the time to draw conclusions: Is God, or is God not, abusive? I admit to having fallen physically ill before writing that section; I just didn’t want to say what the evidence told me to say. But I wrote it anyway (“Being honest entails holding God accountable”). Then came the question, Now what? How does one pray after saying that God can be abusive? I called up the tradition of protest, beginning with Abraham and Job, and continuing through the Jewish poetry of the Crusades and coming right up to Elie Wiesel. And I decided that it was okay to accuse God. Then, I took a very deep breath and plunged into modifying the traditional Jewish liturgy to reflect that stance. The whole book was, and remains, terrifying. Actually using the liturgy that I had composed made me sweat and tremble.

Fellow Jews, even my friends, did not review the book. No one, to the best of my knowledge, ever used the liturgy I had written. Even I got intimidated by it and stopped using it, though, while I recite the traditional liturgy, these thoughts are never far from my intentionality. Survivors of the shoah and of individual physical and sexual abuse were of differing opinions. Some loved the book because it gave them permission to be angry at God; others thought it was blasphemy.

Everyone missed the chapter entitled, “Seriatim, or Sailing Into the Wind.” In that chapter I pointed out that that one cannot sail into the wind. Thus, if one wants to get from point A to point B and the latter is the place from which the wind is coming, one must “tack”; that is, one sails to the right and then to the left, repeating the process as often as necessary, until one gets to one’s goal. Furthermore, if one stays on one “tack” too long, it gets harder and harder to return to one’s course and get to one’s goal. I, then, suggested that many processes in life are like that. All human negotiations proceed by repeatedly moving right and then left until one reaches an agreement and, if one remains too long on one issue, one can never resolve the matter at hand. So it is with prayer, I argued: One must be angry with God and express one’s anger, honestly as Frank says, but one cannot be angry with God for too long or one will get lost in the anger. Rather, one must consciously “tack” in the direction of loving God, but, again, one cannot be loving with God for too long or one will lose the power and honesty of justice.

When I wrote the book, I overstepped some of the traditional boundaries. Still, I think survivors of all kinds of abuse would do well to follow this advice: Be genuinely angry even if it makes you nervous; then, be loving even if it makes you feel compromised; and keep alternating; it is the only way to sail into the wind of that true relatedness to God that we call prayer.