Elizabeth Drescher, Adjunct Associate Professor of Religion & Pastoral Ministry at Santa Clara University, has spent the past several years learning about so-called “Nones”—the religiously unaffiliated who answer “none” when asked with what religion they identify. In a recent conversation with Onnesha Roychoudhuri, Drescher discusses how her interest in this topic developed, the meaning of religious classifications, and the impact of new and social media on how people pray.

Elizabeth Drescher, Adjunct Associate Professor of Religion & Pastoral Ministry at Santa Clara University, has spent the past several years learning about so-called “Nones”—the religiously unaffiliated who answer “none” when asked with what religion they identify. In a recent conversation with Onnesha Roychoudhuri, Drescher discusses how her interest in this topic developed, the meaning of religious classifications, and the impact of new and social media on how people pray.

***

Onnesha Roychoudhuri: What first drew you to studying “Nones” as a religious classification?

Elizabeth Drescher: I was working at a seminary when the 2008 Pew Religious Landscape and the American Religious Identification survey came out. It marked the first big jump in the number of people who identified as religiously unaffiliated. Seminaries were really struggling at that time, as they are now. We were looking at the question of what it meant to prepare people for religious leadership in the current age. I wanted to understand who these folks were and what their relationship to traditional religion was. I wanted to understand how they were developing spiritual lives in relation to and beyond those traditions. So I started there, and I continued to have an interest in what that might mean. Also, I live in northern California. It’s a pretty Catholic culture in many ways, but it’s also really religiously diverse. There are a lot of religiously unaffiliated people.

OR: What are the parameters of the “None” classification? Do many “Nones” consider themselves believers in God?

ED: The data tells us that the majority of the religiously unaffiliated believe in God, a higher power, or something like that. Saying that you’re religiously unaffiliated is saying that you don’t primarily engage or practice that belief in the context of an institutional religious group. But it isn’t to say that you don’t believe in anything.

However, one of the things that the religiously unaffiliated really stress is that our conventional fixation on propositional belief, and those questions that fill our theologies and philosophies—”Is there or isn’t there a God? How does that God work in the world?”—aren’t necessarily the most important measures of how spiritual or religious people are.

For many of the unaffiliated I spoke with, their distance from or indifference to institutional religions didn’t have a whole lot to do with complex doctrinal or theological issues. It had to do with different experiences of the spiritual in their lives that weren’t central to institutional religious practices as they had experienced them.

OR: But it also sounds that you’ve found in your research that many “Nones” are apprehensive to even identify as spiritual.

ED: There’s certainly a range. A sizable percentage of folks from the 2012 “Nones on the Rise” study did identify as spiritual. But many of the unaffiliated—and I think all of the new data from Pew isn’t out, but I suspect that we’ll see this—are religiously indifferent. They are neither religious nor spiritual, and they really don’t want to have their lives defined in that language.

Certainly, the language of the spiritual is often demeaned in the culture—especially the “spiritual but not religious” moniker. I think Lillian Daniel’s work on this is pretty typical. There was a viral essay she wrote for the Huffington Post that she later turned into a book, entitled, “Spiritual But Not Religious? Please Stop Boring Me.” She went on about people who are spiritual as being vapid, narcissistic, and shallow. But what I’ve found is that people have complex ways of understanding what they see as the work of the human spirit, the divine spirit, a natural spirit in the context of everyday life. It wasn’t necessarily systematized in conventional ways, but certainly created a richness in their lives.

OR: I’m curious about all the terminology floating around here. Already, we’ve used the terms “unaffiliated,” and then “Nones.” How much of a role does the categorization and terminology play in the visibility of different ways of practicing spirituality or faith? For instance, I think in the Pew report there was a troubling grouping of different categories.

ED: At one point they lumped together atheists and agnostics, and that creates weird data. You see a certain percentage of people in the atheist/agnostic category who pray, and people think, Well what are you praying to if you don’t believe in God? But, of course, agnostics don’t necessarily not believe in God; they just don’t know that the answer is settled.

The names are really important. When I started doing this research, I had “Nones” as this long hyphenated construction: “Nones—people-who-answer- ‘None’-when-asked-with-what-religion-they-identify-or-affiliate.” Because people didn’t know what that terminology meant. After the “Nones on the Rise” report, which got so much media attention, people suddenly did know. After 2012, people would self-identify to me as “Nones.”

The unaffiliated have tended to be described by the dominant religiously-affiliated cohort as “un” sorts of things: “un-churched,” “un-religious,” “un-saved” or with fairly pejorative language, like “heathens” or “pagans.” Even “atheist” has a strong negative connotation, although that’s changing. “Agnostic” is a little softer. Depending on your denominational background, “humanist” can be more neutral or it can be very negative. So I think for many of the unaffiliated, having this category of “None” allows them to be strategic in how they identify, but it also allows them to say, “I’m not a heathen or an ‘un-churched,’ I’m not nothing. But I’m not what you define.”

OR: It sounds like the term “None” is starting to carve out its own affirmative space. But I when I read the Pew report, I noticed that they were cautious about using the term. They specified that they were putting “Nones” in quotes, as a nod to the fact that the term is considered diminishing by some. What are your thoughts on the use of the term?

ED: For some people, “None” has an empty sound to it, and they want to be more specific. When I was interviewing people for the New Directions in the Study of Prayer project, and for my wider research on the Choosing Our Religion book, I asked them how they identified. I would say, “If someone asked you what your religion is, what would you say? How would you describe yourself?” People had all sorts of ways of describing and labeling themselves, and refusing labels. Sometimes that would change repeatedly in the course of an interview.

One of the things that was pretty consistent was that people would amend the label that they used, often with the space holder, “whatever.” So they might say, “Well, I’m more of an agnostic or whatever.” Some people read that “whatever” in a kind of valley-girl, vapid way. But linguists talk about those kinds of words as space-holders that allow people to negotiate meanings together. Essentially, they’re saying: “There’s not really a word in the language for who I’m being and who I’m becoming, but I’m going to continue to talk about it with you, and maybe together we’ll come up with some kind of understanding.” “Whatever” doesn’t always mean, “it doesn’t matter.”

People have been testing “None” out now for a couple years. For some, it really works well and feels more authentic than something like “spiritual but not religious.” The label will probably change, too. That’s a big part of the process of religious change we’re seeing right now. Just like fixed doctrinal propositional beliefs are no longer the center of people’s religious experience. Even for people who remain affiliated, the language of, “I am a Presbyterian,” or, “I am a Buddhist,” as a fixed feature of identity is less and less the norm.

OR: I know there are a lot of different theories as to why there’s been a rise in “Nones” and an increasing aversion to wholeheartedly embracing one label. What’s your perspective on what might be behind this rise?

ED: There’s no one particular cause. At a really basic level, people live much longer lives than they ever have. As institutional religion was developing, most people died by the time they were 50. They didn’t have a lot of exposure to other religious traditions, and lives were short and brutal. Doing a lot of religious and spiritual exploration was a luxury that most people didn’t have. If you happened to live in a part of the world where everybody was Christian or Muslim or Buddhist, that’s what you practiced. Now, many of us can expect to live past a hundred, and we have much easier lives—even if they’re complex in different ways. Our lifespans allow for a more expansive exploration of religion and spirituality.

New media technologies have given us access to more information and authority over it. And the ability to shape expressions of our identity in online spaces has influenced our offline activity. We have this expectation that everything is revisable in a certain sense. There are very few people with exclusive authority over knowledge, information, and wisdom now. And in a globally connected world, we’re just exposed to lots of different religious traditions and non-religious practices. It’s just not possible, as Charles Taylor tells us, for people—even if they believe in a very devout sense in one particular religious tradition—to really think that other reasonable people don’t believe different things.

People are also frustrated by the politicization of religion, or the religionization of politics, and have stepped away from certain versions of fundamentalist religion and culture. So all of those things have come together to create this period in which people are holding religious identity more loosely and exploring it in more complex ways in their lives.

I think that the conversation itself—about religious affiliation and “Nones”—produces some “Nones.” There are people who might not have been particularly active participants in the religious traditions that they identified with, but maybe still would have said, “I’m a Lutheran,” or “I’m a Hindu.” And when the conversation about “Nones” in the media invites them to think about that, they start identifying as “Nones.”

OR: Your research relies heavily on interviews with “Nones.” Can you talk a little bit about your experience conducting these? Did you discover any common threads in terms of how “Nones” describe prayer, or what constitutes prayer for “Nones”?

ED: I traveled around and interviewed over 100 people across the country about their spiritual lives. There was a lot of variety. When I surveyed people about their spiritual lives, prayer was the only traditional religious practice that came up as spiritually meaningful, consistently across the board—both among the affiliated and the unaffiliated. But people think of prayer in lots of different ways.

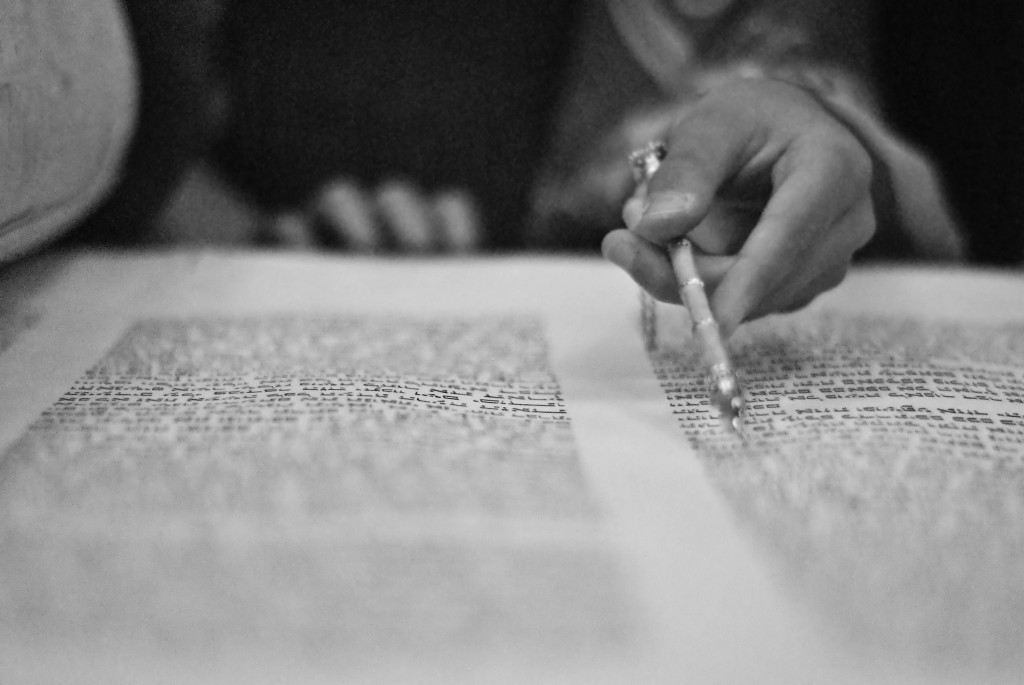

The traditional Judeo-Christian understanding of prayer is that it’s either a petition to a supernatural being, or a way of engaging the presence of that being. So it’s either about making a request and hoping for some kind of change to happen, or developing a relationship, and often expecting some kind of change to happen on the basis of that relationship.

That conception of prayer didn’t come up much with the “Nones” I talked to. More often, I saw prayer functioning as a practice that created a continuity between their religiously-affiliated past and their unaffiliated present. It allowed them to be in certain social relationships—with people in their families, among coworkers and friends who were praying people. For example, one woman I interviewed is an atheist who works as an executive in a social services agency in Chicago. She said that in the course of her work, there are many religious groups and lots of praying. So her feeling is that, Sure, I’ll bust out a prayer, that’s not a big deal. I don’t have to believe in your God to stand with you. She didn’t think the words meant anything in terms of getting a supernatural being to affect lives, but they meant something in terms of her relationships. It’s this idea of praying with people in a Durkheimian sense of creating social cohesion. I’ll pray with you because it brings us together.

This woman also said that when she’s gathering with family and friends, they’ll often start with a prayer as a way of acknowledging the significance of the gathering and the people who are there. For some people there, that has religious meaning, and for others, it doesn’t. I saw that a lot with people I interviewed: prayer serving to continue connections, to move the story forward.

It also came up that prayer held a space in which people could express the paradox of hope and anxiety—often in circumstances where people were praying for somebody. People explained to me that saying you’re praying for somebody is different than saying that you’re thinking about them. When I explored that in greater depth, what I heard was that, when someone is struggling in our lives, we have what I think of as a contingent vulnerability—this sense that your sense of security, safety, and health is connected to mine, at least emotionally. So the idea is, I don’t feel secure and healthy and safe until you are. Prayer is way of narrating that contingent vulnerability and articulating this sense that, I both hope you’ll be better, and I’m worried that you won’t be.

There aren’t many words in our language that really hold that paradox. Saying, “I’ll meditate for you,” or “I’ll think about you” doesn’t say, “I’m implicated in your wellness and security.” Whereas saying, “I’m praying for you” does, even if it doesn’t relate to a supernatural being or force.

OR: What you’re describing sounds like a practice of deep empathy.

ED: Absolutely. People told me that the most spiritually meaningful practices in their life were those that related to family, friends, their pets, and sharing and preparing food. It’s what I think of as the “four F’s” of contemporary spirituality: family, friends, Fido, and food. It’s not necessarily about developing personal virtues that allow you to be a good person in the world; it’s about nurturing relationships, starting with those in the family, relationships with friends, with nature, and so on.

Empathy is really critical in those kinds of relationships of care, where care is the central ethical value. And in that context, prayer is a technology of empathy. It’s a way of articulating and ritualizing empathy. But it also goes beyond that. If empathy is, in a classic dictionary definition, “the ability to understand the feelings of another deeply,” what I’ve been calling “contingent vulnerability” evokes an even deeper compassion, a sense of a profoundly personal implication in the wellbeing of another.

OR: You had mentioned that, for some “Nones,” praying is a way of connecting to their religious pasts. Are there a lot of “Nones” who have a past that includes identifying with a more conventionally delineated religion?

ED: The majority of the unaffiliated come from religious backgrounds—mostly Christian backgrounds. And they emerged from that background in different ways. Sometimes it was problematic, but not always. Some people felt like they took all kinds of beautiful things from the tradition, but that it didn’t really work for them anymore.

One woman I interviewed identifies as variously a “None,” “spiritual but not religious,” and has a pagan-wiccan practice. But she really likes the Episcopal Book of Common Prayer and thinks it’s a beautiful tradition. It’s really common for people to carry artifacts from their tradition into their lives as unaffiliated people.

Another woman I interviewed had a really difficult relationship with her fairly conservative Evangelical tradition. She left it behind and then identified as a fairly hardcore atheist. I think she’s softened on that now, but she talked about prayer as “sneaking up on her.” She really didn’t want to be doing it, but she was in certain life circumstances and it was really the only language she could approach that experience with. But it was uncomfortable for her.

OR: One of the women you interviewed identifies as an atheist, but she starts every morning by praying. And for her, that means looking at photos of her children and grandchildren. And in that instance, it sounds like she’s incorporated that kind of prayer in her life and it’s sufficient. Whereas in some other contexts, it sounds like prayer is an act of yearning to feel connection that isn’t yet fulfilled.

ED: Yes. Judith set out these photos of her daughters and granddaughters every morning. It’s easy to see how that resonates with lots of traditional prayer practices—you know, the prayer cards, having the ritual of doing that every morning. But it’s also easy to see how that doesn’t have to involve an idea of God at all. Just seeing those images reinforces those relationships, deepens empathy, enriches a sense of caring, and creates a sense of fullness for her.

There were other people who talked to me who said, “You know, I wish that I did believe in a God that was going to do something, and when I sit and pray, maybe I’m connecting with something, but I’m not certain about that.” It was still important for them to do. One of the people I interviewed, a recent graduate from Santa Clara where I teach, is an atheist who prays. He says when he does it, he’s not really seeking anything in terms of a specific outcome; he’s just thinking about the people he cares about, the things he wants to explore in his life, his relationship to the world.

OR: You mentioned the impact that new media has had on the conception of “Nones” and prayer. How has the rise of the internet and social media opened up space for a more elastic definition of prayer and the practice of prayer?

ED: We see this on Twitter and Instagram, Pinterest, Tumblr, even Flickr. Every time there’s some kind of tragedy, we see the hashtag on Twitter: #prayforCharleston, #prayforBoston. You’re seeing people expressing this kind of paradoxical understanding of hope and anxiety that is most fully marked in the language we have available with the word “prayer.” It has both some bonding effect—because everybody’s looking at the hashtag—and we’re reflecting on whatever that regional or national experience was. For some, that will provoke what would be traditionally recognized as prayer. They’re going to invoke a deity, petition, use traditional language. For others, it’s going to provoke a kind of reflection that they may or may not consider to be prayer, but we might define as prayerful. It creates a great space.

We see the same thing on more visual sites, where people put up quotes and images that create a kind of digital stained glass window that looks a lot like traditional prayer stations. There’s iconography and short memorable passages that can be recited in patterned ways. People spend time scrolling through them. I have students who say that when they’re feeling down, they go onto Pinterest and scroll around and get some inspiration from people. That certainly changes how people actively experience what they would articulate as prayer or prayerfulness in their everyday lives.

So, they’re not seeing prayer in the more conventional liturgical structures that would be associated with institutional religions. And this isn’t just among the unaffiliated. When the affiliated are going into their churches, they’re also carrying these digitally integrated prayerful practices into those spaces.

OR: Can you give some examples of how these broader conceptions of prayer are evolving the way that people pray in churches?

ED: I think there are lots of churches where ministers are actively inviting people to both Tweet prayer requests or put them on a church Facebook page. So there’s a digitally integrated connectedness that expands beyond the local space into a more distributed network of care. I gave a talk with a colleague a while back, and as an experiment, we invited people in the group to ask for prayer requests. People were holding up their iPads and their iPhones calling out prayer requests from all around the country. It was quite a powerful moment.

Marcel Mauss has an understanding of prayer as increasingly moving people into greater and greater internalization so that, ultimately, we’ll become our own private religious spaces. In fact, social media has flipped that. We’re externalizing prayer quite a lot more,but it’s in much more nuanced ways than, say, a charismatic or street-corner prayer experience. Where we might have seen the evolution of religion becoming more market-based, free choice, individualized, privatized, and interiorized, it’s actually becoming more networked, relational, and social in really complex ways.

We can distinguish three main types of installations for lighting individual candles in Protestant churches. The first is close to the classic Catholic style.

We can distinguish three main types of installations for lighting individual candles in Protestant churches. The first is close to the classic Catholic style.

Anderson Blanton (anthropology), postdoctoral scholar at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, has spent the past several years researching how religious experience is shaped by media technologies and devotional objects. In a recent conversation with Onnesha Roychoudhuri, Blanton discusses how his interest in this topic developed, bureaucracy as a kind of faith, the sacralization of everyday objects, and the “quotidian robustness of religious practice.”

Anderson Blanton (anthropology), postdoctoral scholar at the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, has spent the past several years researching how religious experience is shaped by media technologies and devotional objects. In a recent conversation with Onnesha Roychoudhuri, Blanton discusses how his interest in this topic developed, bureaucracy as a kind of faith, the sacralization of everyday objects, and the “quotidian robustness of religious practice.” Ebenezer Obadare, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, is researching the emergence of what he terms “Charismatic Islam” in Nigeria. Despite the electricity going out just as he started discussing Pentecostal notions of power, Obadare reported from Lagos to Jennifer Lois Hahn on interfaith competition and exchange, political power shifts, and the role of the nation’s largest freeway in the spiritual marketplace there.

Ebenezer Obadare, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, is researching the emergence of what he terms “Charismatic Islam” in Nigeria. Despite the electricity going out just as he started discussing Pentecostal notions of power, Obadare reported from Lagos to Jennifer Lois Hahn on interfaith competition and exchange, political power shifts, and the role of the nation’s largest freeway in the spiritual marketplace there. EO: So the Lagos-Ibadan expressway is easily the most lively, traveled, and busy highway in Nigeria. Over time, because of Nigeria’s traditional problems with maintenance, it fell into disrepair. But it is still the artery that takes you from Lagos, which is a port city, to other parts of the country. So you have to travel on that road. The road is being fixed now, sort of. But that’s beside the point. The point is that at some point it became clear to everybody that in order to be able to establish a presence, you needed a spot on that Lagos-Ibadan Expressway. The first church to do that was the Redeemed Church of Christian God, which established a redemption camp somewhere on the expressway. Part of why the church did that—this has been acknowledged in the literature—was not just to have a physical space that was away from the hustle and bustle of Lagos, but also to signal its own capacity to build a city, a space, that was morally and ethically different from the rest of the country. Initially it was a camp where you would basically go to do the work of spiritual overhauling: you would commune with god, keep in touch with yourself, and undergo the [spiritual?] bath. Over time, the camp became, slowly and then very rapidly after a while, a city by itself. It has its own banks, its own schools. It’s extensive up in there. It’s huge! The centerpiece is the worship center. It’s almost like a Pentecostal Vatican if you will. So the redemption camp became very famous. Every year, they have the Holy Ghost Conference, and people come from every part of the world. I’m talking millions of people. But don’t forget, we’re talking about an expressway that is slowly falling into disrepair. Meaning that every time the Redeemed Christian Church holds a service, things just go crazy on the expressway. Drivers have been caught up in the ensuing anarchy, sometimes for twelve or even 16 hours of absolutely no motion. They can’t go anywhere. It didn’t take the Muslims too long to realize that something was going on here, that this expressway had been claimed by Christians, represented in this case by the Redeemed Church. What they needed to do was not just to contest that space, physically and metaphysically, but to say, “We too can bring traffic to a halt. Look at us. We’re big. We’re mighty! There are millions of us.” So at some point the Muslims decided that the only way they could match what the Christians were doing was to also have their own prayer camp on the expressway. Lo and behold, the Muslim prayer group Nasirul-Lahi-L-Fatih Society of Nigeria (NASFAT) bought a piece of land on the expressway and established their own prayer camp. One of the most symbolic things they did was to engineer their own traffic snarl. It wasn’t an accident. The secretary who I spoke to in the course of my research said, “We did it deliberately.” I asked why and he said, “We wanted them to know that they are not the only ones who can block the highway.” And they did! And a lesson was learned. I recently needed to drive on that road again, and there are tens if not hundreds of churches and mosques on that expressway, on both sides. I’m talking real estate that would blow your mind. There are massive billboards. It’s become a space for every church or mosque to say, “This is who we are. We’re taking a stand. We’re present.” The political battle is carried out here in a special sense with people basically saying the expressway belongs to us, in the same way that they are fighting a battle for the possession of political supremacy in the country.

EO: So the Lagos-Ibadan expressway is easily the most lively, traveled, and busy highway in Nigeria. Over time, because of Nigeria’s traditional problems with maintenance, it fell into disrepair. But it is still the artery that takes you from Lagos, which is a port city, to other parts of the country. So you have to travel on that road. The road is being fixed now, sort of. But that’s beside the point. The point is that at some point it became clear to everybody that in order to be able to establish a presence, you needed a spot on that Lagos-Ibadan Expressway. The first church to do that was the Redeemed Church of Christian God, which established a redemption camp somewhere on the expressway. Part of why the church did that—this has been acknowledged in the literature—was not just to have a physical space that was away from the hustle and bustle of Lagos, but also to signal its own capacity to build a city, a space, that was morally and ethically different from the rest of the country. Initially it was a camp where you would basically go to do the work of spiritual overhauling: you would commune with god, keep in touch with yourself, and undergo the [spiritual?] bath. Over time, the camp became, slowly and then very rapidly after a while, a city by itself. It has its own banks, its own schools. It’s extensive up in there. It’s huge! The centerpiece is the worship center. It’s almost like a Pentecostal Vatican if you will. So the redemption camp became very famous. Every year, they have the Holy Ghost Conference, and people come from every part of the world. I’m talking millions of people. But don’t forget, we’re talking about an expressway that is slowly falling into disrepair. Meaning that every time the Redeemed Christian Church holds a service, things just go crazy on the expressway. Drivers have been caught up in the ensuing anarchy, sometimes for twelve or even 16 hours of absolutely no motion. They can’t go anywhere. It didn’t take the Muslims too long to realize that something was going on here, that this expressway had been claimed by Christians, represented in this case by the Redeemed Church. What they needed to do was not just to contest that space, physically and metaphysically, but to say, “We too can bring traffic to a halt. Look at us. We’re big. We’re mighty! There are millions of us.” So at some point the Muslims decided that the only way they could match what the Christians were doing was to also have their own prayer camp on the expressway. Lo and behold, the Muslim prayer group Nasirul-Lahi-L-Fatih Society of Nigeria (NASFAT) bought a piece of land on the expressway and established their own prayer camp. One of the most symbolic things they did was to engineer their own traffic snarl. It wasn’t an accident. The secretary who I spoke to in the course of my research said, “We did it deliberately.” I asked why and he said, “We wanted them to know that they are not the only ones who can block the highway.” And they did! And a lesson was learned. I recently needed to drive on that road again, and there are tens if not hundreds of churches and mosques on that expressway, on both sides. I’m talking real estate that would blow your mind. There are massive billboards. It’s become a space for every church or mosque to say, “This is who we are. We’re taking a stand. We’re present.” The political battle is carried out here in a special sense with people basically saying the expressway belongs to us, in the same way that they are fighting a battle for the possession of political supremacy in the country.

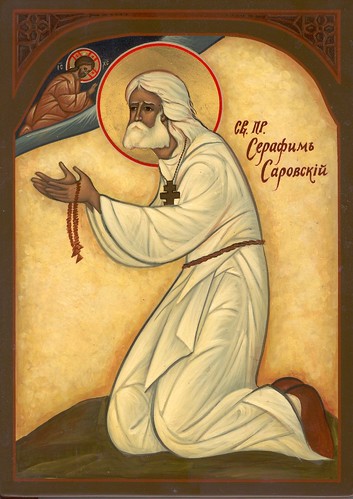

There is an icon that has been created of what is known as the slaughter of the innocents in the West, the incident where King Herod had all these children under two killed in the attempt to kill Jesus, that has been adopted as kind of the symbol of aborted fetuses. There was no traditional iconographic depiction of that scene in its own right. I actually interviewed the iconographer who in the 1990s wrote the first full-size prayer icon of this episode in consultation with a priest. So there are these new prayer media, and there are also official prayers that the church recommends women say for their aborted fetuses. But then there are also ways in which women actually pray for aborted fetuses. The main difference between them is whether or not the women come up with a name for the aborted fetus. The church very emphatically says no, because the only way that a name can be conferred is through baptism, and of course having died before being able to live outside the womb, it is not possible for these children to have been baptized. Whereas there are these unofficial rites that are coming up, by which you actually sort of posthumously baptize your aborted fetus, and then you have a name that allows you to participate in official church prayer. So again, that’s a place where we see that the sensory media and experience is one thing, but the little mark of institutional belonging—do you actually have a baptismal name for someone you want to pray for or not—can become very important in the minds of laypeople, more important than the whole long text that might be around it.

There is an icon that has been created of what is known as the slaughter of the innocents in the West, the incident where King Herod had all these children under two killed in the attempt to kill Jesus, that has been adopted as kind of the symbol of aborted fetuses. There was no traditional iconographic depiction of that scene in its own right. I actually interviewed the iconographer who in the 1990s wrote the first full-size prayer icon of this episode in consultation with a priest. So there are these new prayer media, and there are also official prayers that the church recommends women say for their aborted fetuses. But then there are also ways in which women actually pray for aborted fetuses. The main difference between them is whether or not the women come up with a name for the aborted fetus. The church very emphatically says no, because the only way that a name can be conferred is through baptism, and of course having died before being able to live outside the womb, it is not possible for these children to have been baptized. Whereas there are these unofficial rites that are coming up, by which you actually sort of posthumously baptize your aborted fetus, and then you have a name that allows you to participate in official church prayer. So again, that’s a place where we see that the sensory media and experience is one thing, but the little mark of institutional belonging—do you actually have a baptismal name for someone you want to pray for or not—can become very important in the minds of laypeople, more important than the whole long text that might be around it.

Mark Aveyard, an assistant professor of psychology at the American University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates, is using his knowledge of embodied cognition to study how the position and movement of the body during prayer relates to higher-level cognitive processes such as decision-making, language processing, and emotion. Aveyard, whose work is supported by the SSRC’s New Directions in the Study of Prayer Initiative, recently spoke with Jennifer Lois Hahn about the difficulties of experimental design, WEIRD research subjects, and the impact of culture on the way we think, use our bodies, and in some cases, use our bodies to think.

Mark Aveyard, an assistant professor of psychology at the American University of Sharjah in the United Arab Emirates, is using his knowledge of embodied cognition to study how the position and movement of the body during prayer relates to higher-level cognitive processes such as decision-making, language processing, and emotion. Aveyard, whose work is supported by the SSRC’s New Directions in the Study of Prayer Initiative, recently spoke with Jennifer Lois Hahn about the difficulties of experimental design, WEIRD research subjects, and the impact of culture on the way we think, use our bodies, and in some cases, use our bodies to think. Savitri Medhatul

Savitri Medhatul

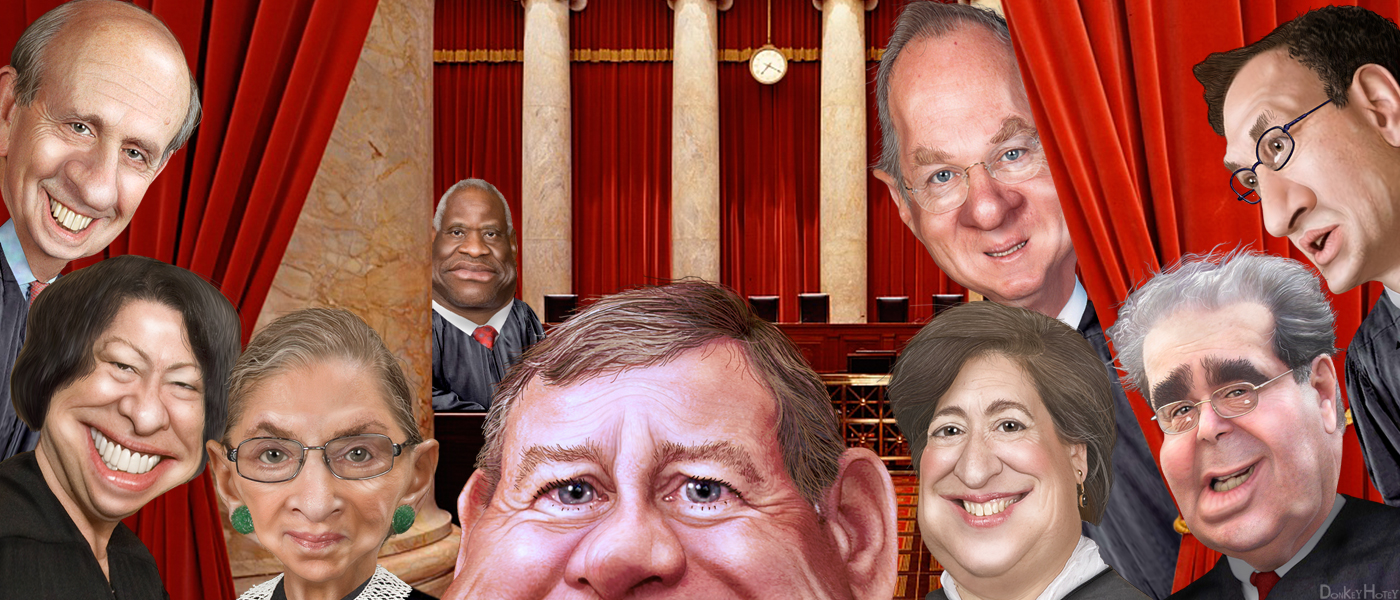

Speaking in the tongue of Christianity in an age of pluralism, the praying citizens of Greece, New York knew enough to keep it vague when bringing their supplications to town council. Winnifred Sullivan’s reflections on the legal wrangling over public prayer in the town council of Greece included examples of how Christians prayed for their town leaders to be “filled with the spirit of wisdom” and asked that their neighbours would come to see the virtues of “interrelationship.” Though recognizably Christian, these prayers addressed to a “Heavenly Father” were nevertheless “tamed by the law,” as Sullivan puts it, in their avoidance of Jesus-language and their studied evasion of deity specificity (except in terms of their gendered language of kinship).

Speaking in the tongue of Christianity in an age of pluralism, the praying citizens of Greece, New York knew enough to keep it vague when bringing their supplications to town council. Winnifred Sullivan’s reflections on the legal wrangling over public prayer in the town council of Greece included examples of how Christians prayed for their town leaders to be “filled with the spirit of wisdom” and asked that their neighbours would come to see the virtues of “interrelationship.” Though recognizably Christian, these prayers addressed to a “Heavenly Father” were nevertheless “tamed by the law,” as Sullivan puts it, in their avoidance of Jesus-language and their studied evasion of deity specificity (except in terms of their gendered language of kinship).

In Orlando, Florida people pin prayers to a cross. The cross stands on the grounds of the

In Orlando, Florida people pin prayers to a cross. The cross stands on the grounds of the

“To our knowledge this is the first time the ‘gift of tongues’ has been recorded.” Liner notes, The Gift of Tongues: Glossolalia LP, Scepter/Mace Records MCM-10040, circa 1960s

“To our knowledge this is the first time the ‘gift of tongues’ has been recorded.” Liner notes, The Gift of Tongues: Glossolalia LP, Scepter/Mace Records MCM-10040, circa 1960s

Years ago, before I was a parent and obsessively risk averse, I took an eventful, if short, research trip. The trip was to northern-central Sri Lanka to visit the quasi-independent region that had been set up by the Liberation Tigers for Tamil Eelam (LTTE), or Tamil Tigers. It was a de facto state complete with its own roads, hospitals, school system, police force, customs officers, ministries and, of course, judicial system. All this was intriguing because the Tamil Tigers were an armed rebel group who since the late 1970s had been fighting a violent campaign against the Sri Lankan state. To most, they were known not for their visa forms and traffic cops, but for their brutal guerilla military tactics and devastating suicide bombings.

Years ago, before I was a parent and obsessively risk averse, I took an eventful, if short, research trip. The trip was to northern-central Sri Lanka to visit the quasi-independent region that had been set up by the Liberation Tigers for Tamil Eelam (LTTE), or Tamil Tigers. It was a de facto state complete with its own roads, hospitals, school system, police force, customs officers, ministries and, of course, judicial system. All this was intriguing because the Tamil Tigers were an armed rebel group who since the late 1970s had been fighting a violent campaign against the Sri Lankan state. To most, they were known not for their visa forms and traffic cops, but for their brutal guerilla military tactics and devastating suicide bombings.

My recent ethnographic fieldwork with an Islamic sect in Turkey focuses on the use of objects during prayer practices, especially prayer beads and their mechanical and digital versions.

My recent ethnographic fieldwork with an Islamic sect in Turkey focuses on the use of objects during prayer practices, especially prayer beads and their mechanical and digital versions.

Munavarbhai is a 42-year-old watch-guard (chokidar) of a middle-class Muslim housing society in a suburb of Ahmedabad, the Indian state of Gujarat’s largest city. His wife Haneiferben does domestic work, but also intermittently works as a house cleaner for Hindu and Muslim middle-class families. Munavarbhai and Haneiferben belong to the informal sector of Ahmedabad’s highly stratified economy. Their nuclear family consists of four heads and has to make do with approximately RS 5,000 a month (roughly US $80). They live in an area of Juhapura called Fatehvadi, in proximity with various rishtedar (relatives) including members of their respective kutumbvala (members of the patriline) interspersed with houses of migrant laborers from outside the state (mostly from Uttar Pradesh) and various other Muslim communities. They hold close social connections with their respective home villages, in which they are officially registered, and to which they regularly return for marriages, festivals, and political elections.

Munavarbhai is a 42-year-old watch-guard (chokidar) of a middle-class Muslim housing society in a suburb of Ahmedabad, the Indian state of Gujarat’s largest city. His wife Haneiferben does domestic work, but also intermittently works as a house cleaner for Hindu and Muslim middle-class families. Munavarbhai and Haneiferben belong to the informal sector of Ahmedabad’s highly stratified economy. Their nuclear family consists of four heads and has to make do with approximately RS 5,000 a month (roughly US $80). They live in an area of Juhapura called Fatehvadi, in proximity with various rishtedar (relatives) including members of their respective kutumbvala (members of the patriline) interspersed with houses of migrant laborers from outside the state (mostly from Uttar Pradesh) and various other Muslim communities. They hold close social connections with their respective home villages, in which they are officially registered, and to which they regularly return for marriages, festivals, and political elections.