The following is an interview conducted by Professor Fareen Parvez and Mariam Awaisi with Juliane Hammer, Associate Professor and Kenan Rifai Scholar of Islamic Studies at UNC Chapel Hill. Professor Hammer specializes in the study of American Muslims, contemporary Muslim thought, women and gender in Islam, and Sufism. She reflects here on the topic of woman-led ritual prayers in Islam and the debate surrounding them.

***

Fareen Parvez and Mariam Awaisi: In your book, American Muslim Women, Religious Authority, and Activism: More Than a Prayer, you discuss the various stakes involved in the debate over woman-led prayers. These include the integrity of the Islamic legal tradition, authority, gender justice, and the politicizing of Islam. This is clearly an important issue. At the same time, it seems to us that we must be careful not to conflate the overall status and well-being of Muslim women across societies with their roles within religious ritual practice. Can you tell us more about the importance of women’s leadership in prayer?

Juliane Hammer: In the book I argue that the debate about woman-led prayer is about more than the question of whether women can, should, or want to lead mixed gender congregations in prayer. In that sense, it is not a matter of conflating issues, but a matter of pointing out that what is at stake in the particular debate about women’s ritual leadership is a larger question about the roles of women in Muslim communities. The answers that constitute the debate come from different actors and represent different perspectives. Thus, for those advocating for women’s prayer leadership, it is a reflection of women’s equality to do so, while opponents point out that women’s rights, safety, integrity, etc. can be achieved without their prayer leadership. It is then a debate about whether leading prayers is representative of women’s status in Muslim communities and societies. In other words, if women are not accepted as prayer leaders, what does that tell us about their status otherwise? Do arguments about why women should not lead prayers, such as their menstrual cycle (women are exempt from prayer during menstruation), the potential temptation that their bodies pose for men praying behind them, concerns about the legal validity of prayers performed behind a woman, etc., tell us something about gender roles and boundaries? Taken to its logical consequence, the debate about woman-led prayer is about what equality might mean and whether different interpretations of that idea (i.e. egalitarianism, different but equal, complementary and equal, and so on), as applied to Muslim communities and societies, are part of God’s intent for humanity. It is, of course, also possible to argue that God did not intend equality for the sexes in the social sphere. It is this distinction between the social and ritual spheres that some argue distinguishes prayers from other aspects of life, while others would say that congregational prayer is simultaneously a ritual and social act. Thus, who can and cannot lead prayers is symbolic of both spheres.

FP and MA: Aside from the issue of leading the ritual prayer, there is also the question of khutbas (“sermons”), typically delivered at jum’ah (“Friday prayers”). Although women may not deliver Friday khutbas in front of a congregation, they may write them and thereby communicate and lead via written format rather than oral. Is this actually practiced in the U.S.? Are these types of avenues embraced by Islamic feminists and activists, or are they viewed as limited in potential?

JH: In the debates outlined above, the two acts are often conflated but they are indeed two different religious acts. There is some legal debate, and thus room, for women to lead at least other women in congregational prayer (not Friday prayer), but traditional legal opinions do not under any circumstances allow women to offer the Friday sermon. The two functions, to lead Friday prayer and to offer the khutba, are not always carried out by the same person either.

While the practice of having women write a khutba and then having a male member of the community read it to the congregation was not part of my research, I have of course come across examples a few times, both in North America and in Germany. Some of the women who do this argue that it is an approach that allows them to stay within their communities and affect gradual change. I would estimate, though, that communities that accept this practice are in the minority; women and men who push for more radical change are often faced with the necessity of leaving their communities and building new ones that reflect agreement on these foundational questions.

As I pointed out above, it is worth asking why a woman’s ideas are acceptable in khutba form. In this case, the problem is not her intellectual ability or religious qualifications, but her physical and aural presence in front of the congregation. More broadly, this is a question of the role of change in religious traditions. Are religious communities and their practices and interpretations constantly changing, as Talal Asad argued when he defined the idea of “discursive tradition”? If that is the case, how do communities determine how much change and in which direction? When do religious communities change so much that they disintegrate? And how much uniformity can one expect from a religious community of over a billion followers?

FP and MA: In many communities, women themselves will say that they desire women-only spaces, that such separation suits their norms and makes them more comfortable. What is the relationship between this, on one hand, and the activism in support of mixed congregations and worship, on the other hand?

JH: You are right—many communities, particularly in North America, have engaged in discussions of women’s spaces. In fact, the initial prompt for Asra Nomani, the lead organizer of the 2005 woman-led Friday prayer in New York, was a change in the construction of the mosque she attended in Morgantown, West Virginia. Thus, for the organizers and participants of the prayer event, the two issues are clearly connected.

At the same time, a good bit of the debate revolved around the distinction between women’s prayer leadership and women’s status, roles, and spaces in mosques. There was much broader consensus on the need for women’s participation in leadership and better prayer facilities as well. Prominent supporters of this type of change included Zaid Shakir, an important American Muslim leader and scholar and Ingrid Mattson,then-president of the Islamic Society of North America (ISNA), which has led more than one initiative about women’s spaces and status in mosques since 2005.

It strikes me that the arguments about women-only spaces are not new. If one traces the study of Muslim women from the early twentieth century to the present, there was a period in the 1980s in which the earlier condemnation of gender segregation made way for very interesting discussions of women-only spaces and single sex dynamics. This exploration had a lot to do with questions of women’s agency and led to some celebration of segregated spaces. At the same time, this is also a younger version of feminist debates and critiques of the distinction between the public and the private spheres, and the ways in which exclusion from the former creates a power differential that is a product of patriarchy. This, then, brings us full circle in our discussions of gender equality.

There is, of course, also a complex nature/nurture debate at play here: do Muslim women who feel more comfortable in segregated spaces feel that way because they have been socialized to? What should communities do with those women who do not feel that way? Can they be accommodated as well? I am reminded of an episode of Little Mosque on the Prairie, a Canadian sitcom written by Zarqa Nawaz that aired on Canadian public TV from 2007 to 2012. In the episode, the small community at the center of the show debates a physical barrier between men and women in the prayer room. After much discussion the imam arrives at a Solomonic solution: a partial barrier. Those women who want to pray behind it can, and those who don’t can pray behind the men.

Perhaps it helps to think of this as a spectrum and to think of different communal practices, and changes to such practices, as situated on this spectrum. There are communities with a long history of shared prayer spaces and others that have long had separate spaces. It is also the case that Muslim women and men attend prayers and other events at mosques that have spatial arrangements they like, and they might stop going to a mosque whose gender management they do not agree with.

FP and MA: It seems that there’s a tension between the need to sustain a social movement around these issues and the consequences that organized movements can entail, such as sensationalized and inaccurate media reporting. This is especially fraught when it comes to Islam. To what extent do you think that greater social change around Muslim women’s mosque participation can occur in this particular global political and media environment? What have you seen to be the main barriers to sustaining a social movement?

JH: I would not want to think of the visibility of Muslim communities as a barrier to sustaining a movement. This is a version of the argument for not airing dirty laundry in public that has been used to slow or stop all kinds of social change. In fact, as I argue in my book, the organizers of the prayer event intentionally utilized media interest to generate intra-Muslim conversation. And that conversation or debate has certainly taken place under the gaze of non-Muslims in the form of various media. I do not think that media attention, or less positively, media bias, has prevented woman-led prayer from becoming a social movement. I am not even sure that was the intent of the organizers. Rather, the prayer event reflected a certain momentum in terms of gender debate and provided that debate with some energy. There are groups and communities in which women and men take turns leading prayers and offering khutbas, and there are communities where that took place before 2005. There are projects, initiatives, and networks of Muslims who work for changes to existing gender practices, including, but also beyond, prayer leadership. And I find it very important to point out that change is directional. It is dangerous to present changes in gender practices as a trajectory towards progress in which Muslims both perpetually play catch up with non-Muslims and in which religion itself easily becomes disposable as part of what holds women back. American Muslim communities produce discourses and practice their religion in a multitude of ways, while often claiming that their discourses and practices are universal and that there is a larger community of Muslims who need to all agree. The reality is much more complex and in my view provides room for debate and for a diversity of practices and interpretations.

FP and MA: Can we say that the struggle for woman-led prayers is a global phenomenon? If so, in what ways do these struggles and successes abroad differ from what we’ve seen in the American context?

JH: I would say no, it is not a global phenomenon by any means. There have been woman-led prayers elsewhere in the world, again, both before and after March 2005. There are global echoes of the debate that took place in 2005, but the event itself is framed more by the American religious landscape and developments in American society than by shared and global Muslim debates about women’s prayer leadership. That is not to say that it is not also part of global discussions among Muslims about gender roles and women’s status in society. It feeds and is fed by such global conversations. But it is precisely in this global framing that other concerns about Muslim women’s safety, welfare, legal equality as well as issues of poverty, racism, war and occupation take precedent over the specific concern with women’s ritual leadership.

In an interesting way, the international responses to the event in 2005 also help us understand the complex relationship between American Muslims as American and as transnational and the ways in which discursive developments among American Muslims are perceived among other Muslims. The organizers of the event were celebrated, but were also branded as agents of American imperialism, bent on undermining Islam and Muslim societies. It is here that the significance and strategic location of American Muslims becomes most evident. The debate thus allowed for important reflections on the role of American Muslims in global Muslim landscapes.

***

Professor Hammer is the author of Palestinians Born in Exile: Diaspora and the Search for a Homeland (2005) and American Muslim Women, Religious Authority, and Activism: More Than a Prayer (2012) and the co-editor of A Jihad for Justice: Honoring the Work and Life of Amina Wadud (with Kecia Ali and Laury Silvers, 2012) and The Cambridge Companion to American Islam (with Omid Safi, 2013). She is currently working on a book project focusing on American Muslim efforts against domestic violence, and on a larger project exploring American Muslim discourses on marriage, family, and sexuality.

The Social Science Research Council’s program on Religion and the Public Sphere announces Why Prayer? A Conference on New Directions in the Study of Prayer (February 6-7, 2015). This two-day gathering will showcase the work of over 30 scholars and journalists exploring what the study of prayer can tell us about a range of topics.

The Social Science Research Council’s program on Religion and the Public Sphere announces Why Prayer? A Conference on New Directions in the Study of Prayer (February 6-7, 2015). This two-day gathering will showcase the work of over 30 scholars and journalists exploring what the study of prayer can tell us about a range of topics. In India, Milad-un-Nabi refers to the celebration of the birth of the Prophet Mohammed. The word milad is the Urdu variation of the Arabic word, mawlid, meaning birth. The Prophet’s birth took place on the twelfth day of the Islamic month of Rab ̄ı’al-Awwal in the Sunni tradition, or the seventeenth day in the Sh ̄ı’ite tradition. Muslims all over the world honor the date, but differently, according to local custom (and,

In India, Milad-un-Nabi refers to the celebration of the birth of the Prophet Mohammed. The word milad is the Urdu variation of the Arabic word, mawlid, meaning birth. The Prophet’s birth took place on the twelfth day of the Islamic month of Rab ̄ı’al-Awwal in the Sunni tradition, or the seventeenth day in the Sh ̄ı’ite tradition. Muslims all over the world honor the date, but differently, according to local custom (and,

![Nellie's Prayer. [In verse...] illustrated by J. Willis Grey | Image via flickr user The British Library](http://forums.ssrc.org/ndsp/wp-content/blogs.dir/23/files/2014/03/11204881576_a2d3dca7b7_b.jpg)

Reverberations is one year old!

Reverberations is one year old!

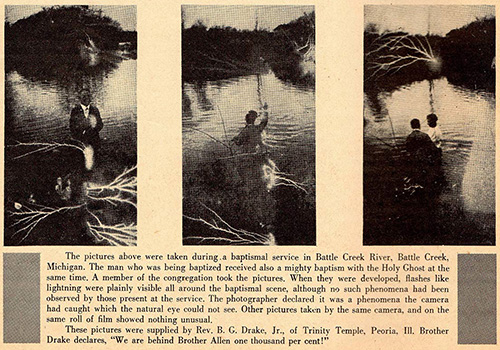

One of the most important biblical references in the history of charismatic faith healing, the story of the woman with an “issue of blood” (Mark 5: 25-34), is often recounted to help explain the communication of curative efficacy from patient to healer. In this classic account of contagion, a woman with a seemingly incurable discharge of blood boldly makes her way through the dense throng following Jesus, reaching out her expectant hand to touch Jesus, the healer. Immediately upon contact with the “hem of his garment,” a healing virtue, or power, is communicated into the woman’s body. Both patient and healer simultaneously register this tactile contact: as the woman experiences a newfound sensation of somatic wellbeing, Jesus feels power leaving his body (see the above illustration from Oral Roberts’ famous

One of the most important biblical references in the history of charismatic faith healing, the story of the woman with an “issue of blood” (Mark 5: 25-34), is often recounted to help explain the communication of curative efficacy from patient to healer. In this classic account of contagion, a woman with a seemingly incurable discharge of blood boldly makes her way through the dense throng following Jesus, reaching out her expectant hand to touch Jesus, the healer. Immediately upon contact with the “hem of his garment,” a healing virtue, or power, is communicated into the woman’s body. Both patient and healer simultaneously register this tactile contact: as the woman experiences a newfound sensation of somatic wellbeing, Jesus feels power leaving his body (see the above illustration from Oral Roberts’ famous

Emphasizing their capacity to

Emphasizing their capacity to  On a basic structural level, the “loudspeaker” is itself a technical reproduction of glossolalia (unintelligible language), one of the most important forms of prayer in the Pentecostal tradition. Focusing upon technological terms such as “loudspeaker,”

On a basic structural level, the “loudspeaker” is itself a technical reproduction of glossolalia (unintelligible language), one of the most important forms of prayer in the Pentecostal tradition. Focusing upon technological terms such as “loudspeaker,”

Stephen Colbert’s mother died last week at 92. His

Stephen Colbert’s mother died last week at 92. His

Underneath the massive cloth architecture of Oral Roberts’ canvas cathedral, the “world’s first healing film” was screened for a crusade audience of over 10,000 on September 29th, 1952. Venture Into Faith is a compilation of actual archival footage shot earlier that year during a healing crusade in Birmingham, Alabama, woven seamlessly into highly produced scenes recorded in a Hollywood studio. The climax of the film, for example, features the miraculous cure of a tubercular boy named David through a performance of prayer. Although the actual performance of this healing prayer was performed by Oral Roberts and a group of professional actors, the final edited version of this spectacle of divine communication oscillates between “live” archival footage shot during a healing campaign and rehearsed “acting” recorded under the careful orchestration of a Hollywood director (1:23:39 in film).

Underneath the massive cloth architecture of Oral Roberts’ canvas cathedral, the “world’s first healing film” was screened for a crusade audience of over 10,000 on September 29th, 1952. Venture Into Faith is a compilation of actual archival footage shot earlier that year during a healing crusade in Birmingham, Alabama, woven seamlessly into highly produced scenes recorded in a Hollywood studio. The climax of the film, for example, features the miraculous cure of a tubercular boy named David through a performance of prayer. Although the actual performance of this healing prayer was performed by Oral Roberts and a group of professional actors, the final edited version of this spectacle of divine communication oscillates between “live” archival footage shot during a healing campaign and rehearsed “acting” recorded under the careful orchestration of a Hollywood director (1:23:39 in film).