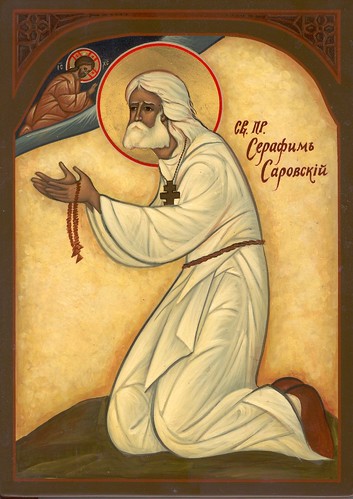

When distinguishing religious from secular activity, contemporary Russian Orthodox believers often draw a contrast between the spiritual and the sensuous. Coming from Byzantine monastic writings that were popularized by nineteenth-century Russian clerics, this contrast refers to two different modes of human existence. Prayer and participation in liturgy are intended to develop the spiritual potential of the human being, moving beyond mere emotion or esthetic enjoyment. Key characteristics that make churches a spiritual space removed from secular sensuality are iconographic styles that depict saints as timeless, serene beings of no particular age, existing in eternity rather than historical time; and liturgical chants that are performed a cappella, in rhythms that are often governed by the words that are sung. The canonical texts of services and hymns to saints also often shy away from the more gory details of their lives and sufferings, to focus on them as spiritual exemplars. But especially when it comes to more popular and lay-oriented forms of praise and prayer, the elements of a liturgical setting can pull in different emotional directions.

When distinguishing religious from secular activity, contemporary Russian Orthodox believers often draw a contrast between the spiritual and the sensuous. Coming from Byzantine monastic writings that were popularized by nineteenth-century Russian clerics, this contrast refers to two different modes of human existence. Prayer and participation in liturgy are intended to develop the spiritual potential of the human being, moving beyond mere emotion or esthetic enjoyment. Key characteristics that make churches a spiritual space removed from secular sensuality are iconographic styles that depict saints as timeless, serene beings of no particular age, existing in eternity rather than historical time; and liturgical chants that are performed a cappella, in rhythms that are often governed by the words that are sung. The canonical texts of services and hymns to saints also often shy away from the more gory details of their lives and sufferings, to focus on them as spiritual exemplars. But especially when it comes to more popular and lay-oriented forms of praise and prayer, the elements of a liturgical setting can pull in different emotional directions.

An example of this are the icon and liturgical texts addressed to the martyr Tatiana (d. ca. 225). The Roman deaconess became patron saint of Russian students by the historical accident that the mother of one of the founders of Moscow University was named Tatiana. In the neo-Byzantine style popular in contemporary Russia, icons of Saint Tatiana (here from a university chapel in Ioshkar-Ola, Volga region) depict her as an unblemished maiden, the cross in her hand the only hint at her sufferings as a martyr.

The troparion verse that is sung as part of the service on Tatiana’s feast day (January 12/25) also spiritualizes her martyrdom. An episode where she was thrown into a lion’s pit becomes a struggle against the “beasts of the mind”:

Following after the Purest Lamb and Shepherd, speaking lamb Tatiana, you were not afraid of the beasts of the mind, but arming yourself with the sign of the cross, conquered them completely, and entered into the Heavenly Kingdom, from whence remember us too, wise martyr of Christ.

But when students attend the service centering around the akathist hymn dedicated to Saint Tatiana offered at many university chapels on a weekday evening, they find a more complex mix of spirituality and emotion. Often coming to pray for successful exams, they face the same imperturbable portrait of the saint and hear the priest and choir take turns in even-tempered chanting. But if they attend to the words recited by the priest and the refrains sung by the choir, they must imagine episodes of martyrdom in all their physical brutality:

Ikos 10:

You were strong as a wall and a diamond, when you were brought to be devoured by beasts, and they did not devour you;

But when they tried to take away the lion it suddenly became enraged and devoured the dignitary Eumenius, showing the power of Christianity. For this reason we pronounce with awe:

Rejoice, who calmed the beasts;

Rejoice, who tamed them through prayer.

Rejoice, who was tortured for Eumenius’s death;

Rejoice, who was hung upon the tree.

Rejoice, who was torn by iron nails;

Rejoice, who was falsely accused of sorcery.

Rejoice, who delivers us from false accusations;

Rejoice, who protects us from evil sorcery.

Rejoice, oh fragrant flower of virginity, glorious martyr Tatiana.

In such paraliturgical texts written mainly by laypeople, sensual and physical drama returns to the prayerful imagination of the faithful, albeit restrained by the tones of the recitation, the archaisms of the Old Slavonic text, and the stylized lines of the icon. Somewhere in between is the prayer request of a student or parent hoping for good marks, left free to see her own tribulations either in a more spiritual or more emotional light.

I heartily welcome Reverberations’s new prayer portal, “Praying With The Senses,” as it not only tackles significant issues in the study of prayer from a variety of methodological angles, but it also brings much needed attention to that which continues to be a significant lacuna in religious studies—namely, the distinctive characteristics of various expressions of Eastern Christian faith and practice.

I heartily welcome Reverberations’s new prayer portal, “Praying With The Senses,” as it not only tackles significant issues in the study of prayer from a variety of methodological angles, but it also brings much needed attention to that which continues to be a significant lacuna in religious studies—namely, the distinctive characteristics of various expressions of Eastern Christian faith and practice.

When distinguishing religious from secular activity, contemporary Russian Orthodox believers often draw a contrast between the spiritual and the sensuous. Coming from Byzantine monastic writings that were popularized by nineteenth-century Russian clerics, this contrast refers to two different modes of human existence. Prayer and participation in liturgy are intended to develop the spiritual potential of the human being, moving beyond mere emotion or esthetic enjoyment. Key characteristics that make churches a spiritual space removed from secular sensuality are iconographic styles that depict saints as timeless, serene beings of no particular age, existing in eternity rather than historical time; and liturgical chants that are performed a cappella, in rhythms that are often governed by the words that are sung. The canonical texts of services and hymns to saints also often shy away from the more gory details of their lives and sufferings, to focus on them as spiritual exemplars. But especially when it comes to more popular and lay-oriented forms of praise and prayer, the elements of a liturgical setting can pull in different emotional directions.

When distinguishing religious from secular activity, contemporary Russian Orthodox believers often draw a contrast between the spiritual and the sensuous. Coming from Byzantine monastic writings that were popularized by nineteenth-century Russian clerics, this contrast refers to two different modes of human existence. Prayer and participation in liturgy are intended to develop the spiritual potential of the human being, moving beyond mere emotion or esthetic enjoyment. Key characteristics that make churches a spiritual space removed from secular sensuality are iconographic styles that depict saints as timeless, serene beings of no particular age, existing in eternity rather than historical time; and liturgical chants that are performed a cappella, in rhythms that are often governed by the words that are sung. The canonical texts of services and hymns to saints also often shy away from the more gory details of their lives and sufferings, to focus on them as spiritual exemplars. But especially when it comes to more popular and lay-oriented forms of praise and prayer, the elements of a liturgical setting can pull in different emotional directions.

During their earthly lives, Coptic saints must preserve their humility and protect themselves from worldly “vainglory” (al-magd al-batil in Arabic). One monk, Abdel-Masih al-Manahri (d. 1963), who hails from a village in the Upper Egyptian municipality of Minya, is fondly remembered among Coptic Christians all over the world for his loud, flamboyant acts of self-effacement. “I want to get married!” “Don’t thank me!” “I don’t know my name!” In the aftermath of his miracles, outbursts like these, of impossible desire and possible insanity, served as warnings to the witnessing public not to seek human recognition at the expense of eternal salvation. For this reason, saints are known to run away and hide from people, preferring anonymity to celebrity.

During their earthly lives, Coptic saints must preserve their humility and protect themselves from worldly “vainglory” (al-magd al-batil in Arabic). One monk, Abdel-Masih al-Manahri (d. 1963), who hails from a village in the Upper Egyptian municipality of Minya, is fondly remembered among Coptic Christians all over the world for his loud, flamboyant acts of self-effacement. “I want to get married!” “Don’t thank me!” “I don’t know my name!” In the aftermath of his miracles, outbursts like these, of impossible desire and possible insanity, served as warnings to the witnessing public not to seek human recognition at the expense of eternal salvation. For this reason, saints are known to run away and hide from people, preferring anonymity to celebrity.  During the elective course “Religion in Contemporary Russia” at the Higher School of Economics in St. Petersburg, undergraduate students discuss the relevance of various classic definitions of religion. Then they are asked to speculate about “minimal religion” in Russian society. The stories about meetings with the sacred which they tell are usually about dead relatives who visited them or members of their kin in a dream shortly after their death. Typically, these dreams are interpreted by the family as an alarming message from the deceased who feels neglected and wants to communicate. As a result, the dreamer goes to church to do her minimal religious work, that is, to light a candle.

During the elective course “Religion in Contemporary Russia” at the Higher School of Economics in St. Petersburg, undergraduate students discuss the relevance of various classic definitions of religion. Then they are asked to speculate about “minimal religion” in Russian society. The stories about meetings with the sacred which they tell are usually about dead relatives who visited them or members of their kin in a dream shortly after their death. Typically, these dreams are interpreted by the family as an alarming message from the deceased who feels neglected and wants to communicate. As a result, the dreamer goes to church to do her minimal religious work, that is, to light a candle.